News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

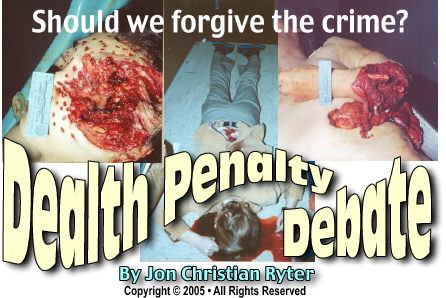

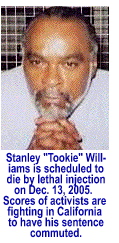

Author's Note (12-13-05): After a lengthy process in which the liberal anti-death penalty advocates fought to have Crips co-founder Stanely "Tookie" Williams spared from the death penalty that was pronounced over him, Williams was executed by lethal injection commencing at 12:01 a.m., Dec. 13, 2005—26 years, 10 months and 11 days after he coldly snuffed out the life of the first of four victims for which he was sentenced to death. The article below was written on Dec. 5—before most Americans knew who Tookie Williams was, or the issues surrounding his battle—and the battle of the liberal advocacy that believes that once the crime fades from memory of the public, the killer deserves clemency. In the case of Williams, the antideath advocates claim he had redeemed himself by writing anti-gang messages in a series of children's books when in fact the books bearing his name as "author" were written by a ghost writer, Barbara Becnel who was, herself, an advocate against the death penalty. Justice has been served for the families of Albert Owens and Yen-l Yang, Tsai-Shai Yang and Yee-Chen Lin.

.jpg)

he

1,000th prison inmate to be put to death since the US Supreme

Court's 10 year moratorium on executions was Kenneth Lee Boyd,

a 57-year old double-murderer. Boyd was executed at 2 a.m.

on Dec. 2, 2005 in North Carolina's Central Prison. Interviewed

by the media on Thursday, Boyd said he did not want to

be remembered by that benchmark—the 1,000th inmate executed.

he

1,000th prison inmate to be put to death since the US Supreme

Court's 10 year moratorium on executions was Kenneth Lee Boyd,

a 57-year old double-murderer. Boyd was executed at 2 a.m.

on Dec. 2, 2005 in North Carolina's Central Prison. Interviewed

by the media on Thursday, Boyd said he did not want to

be remembered by that benchmark—the 1,000th inmate executed.

He doesn't have too much to worry about. A week from now nobody will even remember his name. They may recall the crime. Boyd, a man with a serious drinking problem, was estranged from his wife. She left him because of his love affair with the bottle. He thought she had a boyfriend. In a drunken jealous rage, he broke into his in-laws home in 1988 and, in what was likely argued by his lawyer as a crime of passion, he shot and killed his wife and then, his father-in-law. Aside from the fact that double murderers are generally charged with capital murder, Boyd's crime was particularly heinous since his wife, realizing her estranged husband planned to gun down her whole family, threw her arms around one of her two small sons, protecting his body with hers as she fell to the floor. Boyd stood over her and emptied his gun into her in an attempt, the prosecution argued, to kill his son who was protected by her bloody, bullet-riddled body. I suspect if Boyd is remembered for anything, it will be for this. I know he won't be missed.

The biggest tragedy in the execution of Kenneth Lee Boyd—bigger even than the fact that his two sons were forced to endure the murder of their mother and grandfather—is that it took 17-years for the State of North Carolina to carry out the sentence. Sadly, Boyd's wife didn't get to live an additional 17-years when he sentenced her to death. Neither did her father. His lawyer, in a last ditch appeal to the US Supreme Court, argued that before he committed his double murder, Boyd held down a steady job and had no record of violent behavior. I'm amazed how many "model citizens" are incarcerated on death row in America's prisons. I supposed the fact that he didn't have a violent past somehow made his crime less violent, and mitigated the pain his wife and father-in-law suffered when he callously snuffed out their lives.

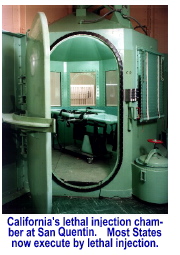

The

debate on execution in America ratchets up whenever a spate of

executions occur or when a "popular" killer like Stanley

"Tookie" Williams is only days from visiting the

gurney in the execution chamber as the advocacy of anti-death

penalty groups in America increase. The debate on the death penalty

is now at a crossroads for several reasons.

The

debate on execution in America ratchets up whenever a spate of

executions occur or when a "popular" killer like Stanley

"Tookie" Williams is only days from visiting the

gurney in the execution chamber as the advocacy of anti-death

penalty groups in America increase. The debate on the death penalty

is now at a crossroads for several reasons.

First,

the debate is once again centered on whether or not the death

penalty is a deterrent to murder. Second, by February, 2005, 120

inmates on death rows around the country have been exonerated—one,

posthumously. That

man was Larry Griffin, who was wrongly convicted of killing

a drug dealer named Quinton Moss in St. Louis on June 26,

1980. Even though the evidence against him was a sham in which

the State's star "eye" witness (who traded his testimony

for a free pass from jail) was not even at the scene of the crime.

Of

course, neither was Griffin. Griffin was in another

part of the city helping a friend sell a boat. Unfortunately for

Griffin, while all of the parties remember the transaction

occurring on June 26, the buyer of the boat dated his check for

the 27th, and the prosecution argued that the boat sale was a

day after the killing. Griffin

was convicted with perjured testimony and executed for

a crime he did not commit. Because St. Louis detectives had a

"gut instinct" that Griffin was the killer (since

Moss killed his brother), their investigation consisted

only of making sure the evidence fit the the man they believed

was guilty. Because of that, several eyewitnesses that were there

and saw Moss gunned down, were never interviewed by St. Louis

police.

Of

course, neither was Griffin. Griffin was in another

part of the city helping a friend sell a boat. Unfortunately for

Griffin, while all of the parties remember the transaction

occurring on June 26, the buyer of the boat dated his check for

the 27th, and the prosecution argued that the boat sale was a

day after the killing. Griffin

was convicted with perjured testimony and executed for

a crime he did not commit. Because St. Louis detectives had a

"gut instinct" that Griffin was the killer (since

Moss killed his brother), their investigation consisted

only of making sure the evidence fit the the man they believed

was guilty. Because of that, several eyewitnesses that were there

and saw Moss gunned down, were never interviewed by St. Louis

police.

And finally, the Washington Post, New York Times and several other large metro newspapers have reported that serious problems have been uncovered in the FBI's DNA laboratory, with the Justice Department admitting that the results from several hundred DNA tests in rape and murder cases conducted by the FBI are probably wrong. In their "zeal" to help local prosecutors convict those who the local police say are the bad guys, the FBI's forensics people have not been quite as diligent as they should have been in matching genetic codes. "Close" works in horseshoes, but not in DNA—particularly when lives depend on the accuracy of that analysis.

Ask

Robin Lovitt. Lovitt was convicted of the 1999 stabbing

death of Clayton Dicks, the night manager of a Virginia

pool hall. From the moment he was arrested, Lovitt maintained

his innocence.  The

crime was committed with a pair of scissors. Police found blood

on the scissors and—they said—on Lovitt's jacket.

The evidence was sent to the FBI who said it was a match. After

a speedy trial, Lovitt was convicted and sentenced to death.

The

crime was committed with a pair of scissors. Police found blood

on the scissors and—they said—on Lovitt's jacket.

The evidence was sent to the FBI who said it was a match. After

a speedy trial, Lovitt was convicted and sentenced to death.

During the trial the prosecutor argued that DNA evidence showed that Lovitt handled the murder weapon, and that Dicks' blood on Lovitt's jacket proved he was the killer. The jury bought the argument. After all, DNA is never wrong. It's the genetic blueprint of the person. But, DNA is correct only when the forensic scientists who read the code are diligent in matching the genetic strands found on the suspect with the DNA of the suspect. In Lovitt's case, the test results were inconclusive. They simply did not support the argument of the prosecution—and the prosecution knew it. But, once again, the local police were convinced they got the right man and everyone in the criminal justice system did what they could to oblige them.

When a petition for clemency for Lovitt were sent to the office of Democratic governor Mark Warner. The governor wanted to review the DNA evidence in the Lovitt case, only to discover that the trial judge ordered all of —including the murder weapon and Lovitt's jacket—destroyed. Defending the magistrate, the senior court clerk who prepared the order under the judge's name said he, not the judge, ordered the evidence destroyed. He did it, he said, believing, that it was no longer needed since the case was over.

In defending the actions of the senior clerk, the newly elected Attorney General of Virginia attempted to diminish the value of the DNA evidence by suggesting that Lovitt's conviction came from eye witness testimony and not from questionable DNA evidence. The eye witness, however, was a man who admitted under oath prior to the trial that he couldn't see the assailant's face. When he was asked to identify the killer during the preliminary hearing, the witness admitted he couldn't be sure it was Lovitt because the crime happened "...a long time ago and he saw the [killer] only for a couple of seconds." At trial, the same witness was "...80% sure" because, he said, "...everytime I see him, he looks more like the person I saw." Lovitt was actually fingered by a jailhouse snitch with an axe to grind who was looking for privileges in exchange for his testimony against Lovitt. The odds are very good that Lovitt is an innocent man whose death sentence was just commuted to life in prison without a chance for parole. Unlike Larry Griffin, Lovitt will still be alive when some honest prosecutor exonerates him.

While

Griffin and Lovitt offer excellent arguments for

abolishing the death penalty, Tookie Williams, Eric

Nance, John Hicks and Joseph Smith are prime

examples of why the death penalty exists, why it is needed, and

why it should be used without interference from social justice

advocates.

While

Griffin and Lovitt offer excellent arguments for

abolishing the death penalty, Tookie Williams, Eric

Nance, John Hicks and Joseph Smith are prime

examples of why the death penalty exists, why it is needed, and

why it should be used without interference from social justice

advocates.

Jurors in the murder trial of Joseph Smith—who raped and murdered 11-year old Carlie Brucia in Sarasota, Florida after security cameras at a car wash captured the 39-year old mechanic as he kidnapped the girl on Feb. 1, 2004—had all the "eye-witness" evidence they needed to find the defendant guilty . The video, if you recall, was broadcast worldwide. There was no place Smith could hide. He was quickly identified and apprehended. After finding Smith guilty of kidnapping, first degree murder and sexual battery on a child, the jury deliberated a second time, on Dec. 1, 2005 for five hours and, by a vote of 10 to 2, recommended the death penalty.

Smith's attorney, Adam Tebrugge, argued that Smith was high on either heroin or cocaine when he ran into Brucia taking a shortcut through the parking lot behind the car wash. In the penalty phase, Tebrugge argued that Smith should be given a life sentence without parole. That would be, he said, "...a fitting conclusion to this horrific case. The Joe Smith on Feb. 1, 2004 was a man in pain, ravaged by drug abuse and out of control. The Joe Smith—the drug addict—who was out of control will never exist again because he will be kept away from drugs." A fitting end for Smith would be a swift and painful execution. Neither will happen. By the time Smith has exhausted all of his appeals, and by the time the anti-death penalty advocates delay the process, no one but her family will remember Carlie Brucia. His lawyers, a couple of decades later, will argue that the 60-year old Smith no longer poses a threat to society. Only her mother will grieve over the miscarriage of justice as the societal do-gooders paint the names of wrongly-executed inmates on placards as if to suggest that, just possibly, Smith did not get a fair trial.

At the conclusion of the penalty phase of Smith's trial, Brucia's mother, Susan Schorpen, summed it for every mother who was ever haunted by the memory of a violated, murdered daughter: "He may be condemned, but he's still breathing and my daughter is not." Justice for the Schorpen family will not come until Smith stops breathing. Smith did not hesitate a moment in taking Carlie Brucia's life. Why should her mother have to wait one or two decades for Smith to stop breathing? Where is her justice?

This is part of the reason that the death penalty is not the deterrent to murder that it should be. Anyone weighing the consequences of premeditated murder knows the odds of his or her ever being executed are fairly remote—assuming, first, that they are caught. It generally takes up to 20 years to execute a condemned prisoner. If the family members of the victim die before the killer, the odds for clemency increase exponentially.

Those convicted of capital offenses know that even if they are convicted, the odds are 50/50 that they will be sentenced to die. Once they arrive on death row, the odds of the execution actually being carried out are less than 50%—which suggests that only about 25% of who are convicted of first degree murder will be executed for their crime. A large percentage of those who are executed live a normal lifespan before the execution is carried out. If anyone suggests to you that a lifetime behind bars is worse than being executed, they're blowing smoke at you. If they were condemned to death and were about to be executed, I assure you that if they could exchange their death sentence for life behind bars, every one of them—without exception—would do it in a heartbreat...something their victims no longer possess. That's why commuting the death sentence of Crips gang founder Stanley "Tookie" Williams won't exact the penalty for the four lives snuffed out by Williams during two robberies in February and March, 1979 that the people of Los Angeles county demanded at his trial.

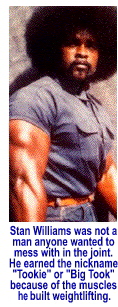

In 1971, a 17-year old Williams and his friend Raymond Washington, founded what became known the Crips in Los Angeles. In the ensuing decade, the Crips became LA's deadliest street gang and its biggest distributor of cocaine and heroin. It didn't take long before imitators sprang up all over the country, emulating the As he attempted to sanitize his image by changing the motives for his past, Williams recalled that he and Washington were fed up with all the random violence in South Central LA and decided to do something about it. What they decided to do, Williams said, was to "...cleanse the neighborhood of all these—you know—marauding gangs. Eventually," he concluded, "we morphed into the monster we were addressing."

On

February 27, 1979 Williams ordered two of his gang members

(identified only as Darryl and Sims) to rob a Stop-N-Go

Market just off the freeway in Pomona, California. The pair

entered the store armed with a .22 handgun. As Darryl approached

the store clerk for cigarettes, Sims proceeded to the back

of the store to check if any other employees on duty. Hearing

someone else in the back, Sims turned and left the store.

Darryl followed him.

On

February 27, 1979 Williams ordered two of his gang members

(identified only as Darryl and Sims) to rob a Stop-N-Go

Market just off the freeway in Pomona, California. The pair

entered the store armed with a .22 handgun. As Darryl approached

the store clerk for cigarettes, Sims proceeded to the back

of the store to check if any other employees on duty. Hearing

someone else in the back, Sims turned and left the store.

Darryl followed him.

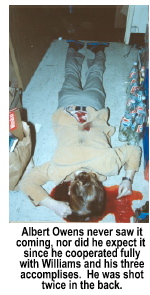

Williams

became angry because they failed to rob the store. He told them

he'd find another place to rob. All of them would go, Williams

said, so he could show them how it was done. In a stroke of bad

luck for 7-Eleven manager Albert Owens at 10437 Whittier

Boulevard in Pico Rivera, Williams chose him. As Darryl

and Sims entered the 7-Eleven, Owens, who was sweeping

the parking lot, placed his broom and dustpan on the hood

of his own car and followed them into the store.  Williams

and Alfred Coward, the 4th gang member, followed Owens.

Once inside the 7-Eleven, Williams pulled a sawed-off shotgun

from under his coat. He pressed it into Owens back and

told him to "...shut up and keep on walking."

Once in the backroom, Williams fired twice at close range,

killing Owens. The robbery netted Williams $120.00

in cash.

Williams

and Alfred Coward, the 4th gang member, followed Owens.

Once inside the 7-Eleven, Williams pulled a sawed-off shotgun

from under his coat. He pressed it into Owens back and

told him to "...shut up and keep on walking."

Once in the backroom, Williams fired twice at close range,

killing Owens. The robbery netted Williams $120.00

in cash.

Back in the car Sims asked Williams why he killed Owens. "Because he was white," Williams said, adding that he was going to kill all white people. Then he said he just didn't want to leave any witnesses behind. "You should have heard the way he sounded when I shot him," Williams laughed, making a gurgling sound.

The

second robbery for which Williams was convicted took place

at the Brookhaven Motel in South Central LA. Court transcripts

indicate that Williams entered the motel on South Vermont

Avenue around 5 a.m. on March 11, 1979. He walked directly to

private office in rear of the lobby area and kicked in the door,

startling the owner, Yen-l Lang, his wife Tsai-Shai

Yang and their daughter, Yee-Chen Lin. The two women

screamed. Without any provocation, Williams opened fire,

killing all three members of the Yang family.  When

the autopsy was done on Yen-l Yang, the plastic container

from the shotgun shell was recovered near his liver. The pathologist

noted during the trial that the anomoly happened because the shotgun

was held cose to the victim when he was shot. Williams

then shot Yee-Chen Lin in the face. Williams rammed

the barrel of the shotgun into the buttocks of Tsai-Shai Yang—after

his first shot hit her in the abdomen—as she struggled to

turn to flee. He fired again. Both the wadding from the shotgun

shell and the plastic shot container were recovered from Tsai-Shai's

body. The second shot shattered her coccyx (tail bone). This crime

was particularly heinous because of the coldbloodedness of the

killings.

When

the autopsy was done on Yen-l Yang, the plastic container

from the shotgun shell was recovered near his liver. The pathologist

noted during the trial that the anomoly happened because the shotgun

was held cose to the victim when he was shot. Williams

then shot Yee-Chen Lin in the face. Williams rammed

the barrel of the shotgun into the buttocks of Tsai-Shai Yang—after

his first shot hit her in the abdomen—as she struggled to

turn to flee. He fired again. Both the wadding from the shotgun

shell and the plastic shot container were recovered from Tsai-Shai's

body. The second shot shattered her coccyx (tail bone). This crime

was particularly heinous because of the coldbloodedness of the

killings.

Much

of the damning evidence against Williams came from his

acquaintances. When Williams was interviewed by the police,

he knew details of both robberies that only someone involved in

them would know, since many of the details Williams mentioned

when he was questioned were never released to the media and could

only have been known by the person who committed the murders.

Williams, to this day, insists he is innocent. Over the

years, he has alleged: [1] biased jury selection, [2]

exclusion of exculpatory evidence, [3] ineffective

counsel, [4] misuse of jailhouse and government informants,

and [5] prosecutorial misconduct. Williams insists

he should never have been arrested because the police had no fingerprints,

no blood transfers on his clothes, no eyewitnesses and no other

crime scene evidence that linked him to the crimes.

Much

of the damning evidence against Williams came from his

acquaintances. When Williams was interviewed by the police,

he knew details of both robberies that only someone involved in

them would know, since many of the details Williams mentioned

when he was questioned were never released to the media and could

only have been known by the person who committed the murders.

Williams, to this day, insists he is innocent. Over the

years, he has alleged: [1] biased jury selection, [2]

exclusion of exculpatory evidence, [3] ineffective

counsel, [4] misuse of jailhouse and government informants,

and [5] prosecutorial misconduct. Williams insists

he should never have been arrested because the police had no fingerprints,

no blood transfers on his clothes, no eyewitnesses and no other

crime scene evidence that linked him to the crimes.

Although he has apologized for founding the Crips, Williams has never renounced his allegiance to the gang. He spent 6 1/2 years in solitary confinement during the late 1980s for assaulting fellow inmates and guards. In 2001 a Swiss member of Parliament, Mario Fehr, nominated Williams for a Nobel Peace Prize for Literature for writing children's books warning kids about getting into gangs. No mention was made of the fact that the real author of his books was journalist Barbara Becnel who served as his ghost writer-editor. In 2004 Williams—from his prison cell—helped broker a peace agreement between the Crips and the Bloods. Williams received a letter from President George W. Bush commending him for his community activism.

In 2002 Williams appeared before a 3-judge panel of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals in an attempt to have his conviction overturned. The panel upheld his conviction—pretty much negating Williams' claims that he did not receive a fair trial. In a letter to then California Gov. Gray Davis, the judges lauded Williams' efforts in opposing gang violence and asked Davis to consider commuting Williams' death sentence. Davis, who clearly understood the nature of the crimes committed by Williams, would not commute his sentence for the same reason the 9th Circuit wouldn't overturn his conviction. Not only was Williams guilty of four very cold-blooded killings, it appeared to those who studied him that Williams took a particular delight in killing. He was a man without remorse and without a conscience. Among those petitioning the State to carry out the execution of Williams on Dec. 13 was the LAPD.

Since Jamie Foxx played Williams in a made-for-TV movie based on Williams autobiography, Redemption, pressure mounted from the Hollywood crowd and elitist far left on Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger to grant clemency to Williams. When they meet on Dec. 8, it is likely his sentence will be commuted. A commutation of his sentence will deny both closure—and justice—to Robert Yang and his wife, who were sleeping in their bedroom at the Brookhaven Motel when Williams shot his father, mother and sister. Yang found the bodies of his father, mother and youngest sister. The scene in the office of the Brookhaven Motel is an indelible image he will carry in his mind for the rest of his life.

When

John Hicks—the 999th inmate executed since the death

penalty was reinstated, Douglas Hughes, an uncle of 5-year

old Brandy Green—one of the two people killed by Hicks—said

the execution finally gave him closure. He also said he was disappointed

with Hicks' deathbed statement. he claimed Hicks'

showed no real remorse and never apologized to the families of

his victims, Maxine Armstrong, his mother-in-law and Brandy,

his stepdaugher, nor asked anyone's forgiveness for killing them.

"Twenty years did nothing to change the way he felt about

taking her life," Hughes said. Hicks had

been on death row since 1986 for killing his 56-year old mother-in-law,

and then suffocating his 5-year step daughter to hide the crime.

When

John Hicks—the 999th inmate executed since the death

penalty was reinstated, Douglas Hughes, an uncle of 5-year

old Brandy Green—one of the two people killed by Hicks—said

the execution finally gave him closure. He also said he was disappointed

with Hicks' deathbed statement. he claimed Hicks'

showed no real remorse and never apologized to the families of

his victims, Maxine Armstrong, his mother-in-law and Brandy,

his stepdaugher, nor asked anyone's forgiveness for killing them.

"Twenty years did nothing to change the way he felt about

taking her life," Hughes said. Hicks had

been on death row since 1986 for killing his 56-year old mother-in-law,

and then suffocating his 5-year step daughter to hide the crime.

Hicks

received a 30-year sentence for a second degree murder of Maxine

Armstrong and the death sentence for the premeditated murder

of Brandy Green.

Hicks

received a 30-year sentence for a second degree murder of Maxine

Armstrong and the death sentence for the premeditated murder

of Brandy Green.

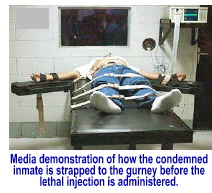

As he lay strapped to the gurney, Hicks' said: "I know it's been 20 years of pain and hurt, but during that 20 years I suffered, too. I cared, and loved, too, for Maxine and Brandy. God has forgiven me," he said. "I'm sorry and I wish I could bring them back." Hicks, who was trying to steal drug money from his mother-in-law when she caught him, added: "It began with a syringe in my arm and this day is ending with a needle in my arm. Its come full circle."

A 2004 Gallup poll found that support for the death penalty in the United States is waning even though a large majority of Americans still favor using it even though, Gallup said, only 35% of the population believes the death penalty serves as a deterrent to murder. Those, the pollsters say, who favor the use of the death penalty do so not as a deterrent to murder but simply as punishment. An eye for an eye. Capital punishment advocates don't believe the American people should be saddled with the enormous cost of keeping murderers alive. I agree.

Hicks' lawyer, Marc Mezibov said the execution was a "senseless killing" because the John Hicks that killed Armstrong and Green was not the same John Hicks that was strapped to the gurney on November 29, 2005. Mezibov said the old Hicks was a cocaine addict and it was the cocaine psychosis that was responsible for the deaths of his victims.

Because

so much time normally elapses between the trials and convictions

of murderers and their executions, the public din at the outrage

of their crimes has long faded from the memories of the public,

and the indignation is now forgotten.  Thus,

when the advocates of social justice drag out their soapboxes

and protest the outrage of capital punishment as they portray

the killers as the victims, few advocates of justice step up to

mourn the real victims—those who lives were stolen from them

by greedy men and women without of shred of regard for human life

until their own life hangs in the balance. "Since 1979,"

Michael Paranzino, president of Throw Away The Key—a

group that supports the death penalty—said, "we've

had 100 thousand innocent people murdered in the United States.

But nobody is planning on commemorating [them]."

Thus,

when the advocates of social justice drag out their soapboxes

and protest the outrage of capital punishment as they portray

the killers as the victims, few advocates of justice step up to

mourn the real victims—those who lives were stolen from them

by greedy men and women without of shred of regard for human life

until their own life hangs in the balance. "Since 1979,"

Michael Paranzino, president of Throw Away The Key—a

group that supports the death penalty—said, "we've

had 100 thousand innocent people murdered in the United States.

But nobody is planning on commemorating [them]."

America's problem is that the social justice elites who are able to mitigate the crimes of the miscreants expect the victims of crime to simply forgive and forget. We are, after all, still a Christian society, and while the liberals want to banish Jesus Christ from our lives, our communities and our nation, they still expect us to turn the other cheek and forgive those who trespass against us. Sometimes forgiveness comes hard—as it did for the family of Julie Heath in 1993.

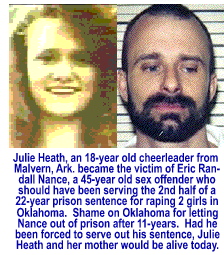

An 18-year old Malvern, Arkansas cheerleader, Julie Heath, was driving home from from visiting her boyfriend in Hot Springs late in the evening on Oct. 11, 1993 when her car broke down in Highway 270. Eric Randall Nance, who was returning to Hot Springs from Malvern, stopped when he saw the stranded redhead. It appears from the evidence that Nance offered to give Heath a lift to Malvern. When she got into his pickup truck, every woman's worst nightmare came true. Nance held a box cutter to her throat and forced her to undress. It appears that, as he tried to rape her, she decided to fight back. It would prove to be a fatal fight for Heath. No match for a 45-year old male, Nance slit her throat with the box cutter.

Nance

drove his truck off the paved highway onto an unpaved road that

led into the woods where he disposed of the body.  He

apparently was not worried about being seen since he took the

time to put Julie's clothes back on her dead body. In the

dark, he didn't realize that her shirt was inside out, as were

her panties and her socks. Heath was having her period

because, near her body was a used sanitary napkin. On Oct. 18,

a hunter discovered her fully clothed body in the woods. Because

of a prior history as a sexual predator, and because a witness

saw him that evening along Hwy 270, Arkansas police picked Nance

up for questioning. They arrested him two days later. Crime scene

investigators found several red pubic hairs in the cab of Nance's

truck. Forensic testing of the pubic hair found in the truck matched

the pubic hair of the dead girl.

He

apparently was not worried about being seen since he took the

time to put Julie's clothes back on her dead body. In the

dark, he didn't realize that her shirt was inside out, as were

her panties and her socks. Heath was having her period

because, near her body was a used sanitary napkin. On Oct. 18,

a hunter discovered her fully clothed body in the woods. Because

of a prior history as a sexual predator, and because a witness

saw him that evening along Hwy 270, Arkansas police picked Nance

up for questioning. They arrested him two days later. Crime scene

investigators found several red pubic hairs in the cab of Nance's

truck. Forensic testing of the pubic hair found in the truck matched

the pubic hair of the dead girl.

Confronted with this evidence, Nance admitted picking her up on Hwy 270. He told police he agreed to drive her back to Malvern. He said as they were driving, she saw the box cutter and became hysterical. Nance said she started hitting him and pulling his hair. He claimed when he put his hand up, defensively, to ward off her blows, the blade got wedged in her throat and killed her. Over the objections of defense counsel, the prosecution presented, as evidence, six prior felony convictions resulting from Nance's rape and beating of two Oklahoma girls in 1982.

After serving half of a 22-year prison sentence, the State of Oklahoma released Nance from their penal system in May, 1993 and let him slip through the crack—five months before he killed Julie Heath in Arkansas. Nance was a sexual predator. He should never have been released from any penal institute until every hour of his sentence was served. And then, the State still had an obligation to keep the public safe from that predator.

There was a double tragedy in the murder of Julie Heath on Oct. 11, 1993. When she testified at Nance's sentencing hearing, Nancy Heath, Julie's mother told the court, "Mr. Nance took my only daughter. I have been under constant doctor's care since her death. I've been to see a psychologist once a week. I'm on numerous medications. My life will never be the same again. This has affected all of my family. It's been very hard on my husband and son. We basically don't know how we can live without her..." Nancy Heath couldn't.

After struggled through the holidays of 1993, Nancy committed suicide shortly before Christmas, 1994 telling her family in the note she left behind that she could not endure another Christmas without Julie. Eric Randall Nance killed both women, but he only paid for the death of one of them. For killing Julie Heath, Nance paid the supreme price on Nov. 28, 1995. He was the 998th murderer executed since the reinstatement of the death penalty.

The claims of the anti-death penalty advocates that capital punishment is not a deterrent to murder—based on polls people taken by anti-death penalty advocates—is sheer, biased nonsense.

How many people have been discouraged from killing a spouse, a business rival, or a nasty neighbor because they knew if they were convicted of capital murder they would face the death penalty? We don't know. Why not? First, because those crimes did not happen. Second, because those who have entertained such thoughts, regardless how fleeting they may have been, are not likely to candidly admit they actually considered killing someone. They may jokingly say they did because some people—well, they just get under your skin. But those who have seriously weighed the option will likely never admit it since the possibility exists that, sometime in the future, the opportunity to escape judgment might make the crime worth the gamble.

Likewise, keeping condemned murderers and rapists alive for two or more decades punishes the taxpayers who are forced not only to pay for the incarceration of people who should have been speedily executed, it also forces the taxpayers to foot the bill for countless appeals to higher State courts, US District Courts, appellate courts and, in some cases, the US Supreme Court. The legal bills, paid by the taxpayers. is staggering. By the time an inmate has exhausted every legal avenue he or she can explore to escape the death penalty, we will have coughed up a million dollars or more for their attempt to evade the sentence we imposed. That doesn't make sense to me. How about you?

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.