News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet

Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

When

the State screws up and

executes the wrong person,

how do you "fix it"?

I

have long been a proponent of capital punishment. Nothing has happened

to change that view even though a recent acknowledgment by St. Louis,

Missouri Circuit Prosecutor Jennifer Joyce has clearly established

that the State of Missouri may well have executed a man who was innocent

of the murder for which his life was taken by that State.

I

have long been a proponent of capital punishment. Nothing has happened

to change that view even though a recent acknowledgment by St. Louis,

Missouri Circuit Prosecutor Jennifer Joyce has clearly established

that the State of Missouri may well have executed a man who was innocent

of the murder for which his life was taken by that State.

In my "death

penalty advocacy," I have also long advocated that we change the

appeals process of the criminal justice system to a policy of peer review

to "double check" the conduct of the court and the integrity

of both the prosecution and the defense to make sure that those accused

of murder receive not only a fair and impartial trial but an honest

one as well. Once an appellate court determined from the peer review

that the accused was honestly convicted, the sentence of the court would

then—and only then—be carried out. Swiftly. No convicted

murderer would have the luxury of living on death row for 10 to 20 years,

using up taxpayer dollars filing an endless stream of appeals until

the US Supreme Court either permanently stayed the execution or granted

a new trial. And, while I would make capital murder a federal crime

with a mandatory death penalty, no person could face the death penalty

in a case in which the conviction hinged on circumstantial evidence;

nor

could anyone be executed without a DNA match that proves, well beyond

a shadow of doubt, that he or she—and no one else—is guilty

of the crime for which he or she has been sentenced to death.

nor

could anyone be executed without a DNA match that proves, well beyond

a shadow of doubt, that he or she—and no one else—is guilty

of the crime for which he or she has been sentenced to death.

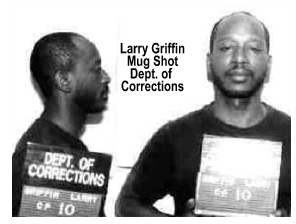

Had Larry Griffin received such a trial—and a peer review of the evidence presented at his trial—it is likely his conviction would have been overturned. In any event, even if Griffin was not exonerated by the peer review, there was no DNA evidence to examine, thus, under my scenario, he could not have received the death sentence and would still have been alive ten years after his execution when a curious prosecutor reopened the case because some of the things she stumbled across screamed, out loud, that Larry Griffin was not any of the three men in a 1968 Chevy Impala who shot a 19-year old drug dealer and street gang-assassin Quintin Moss 13 times on the corner of Sarah Avenue and Olive Street in the crime-infested area of St. Louis known as "The Stroll" on June 26, 1980, killing him almost instantly.

First,

let me say this about Larry Griffin. He was a bad man. He needed

to be locked up and kept away from society. Not for killing Moss,

since he didn't kill him. Griffin, like Moss, was a career

criminal who fed on society like a leach. Society, quite bluntly, is

better off without either of them. But simply dismissing them as worthless

members of society does not mitigate what happened in "The Stroll"

that afternoon in June, 1980.

First,

let me say this about Larry Griffin. He was a bad man. He needed

to be locked up and kept away from society. Not for killing Moss,

since he didn't kill him. Griffin, like Moss, was a career

criminal who fed on society like a leach. Society, quite bluntly, is

better off without either of them. But simply dismissing them as worthless

members of society does not mitigate what happened in "The Stroll"

that afternoon in June, 1980.

The concept of justice in any society governed by the rule of law demands that the justice system not deliberately frame bad people simply because they are bad. If we were allowed to lock up bad people simply because they were bad, there wouldn't be a politician left in Washington (since every politician who takes a contribution from a special interest group or lobbyist who has reasonable expectation of a quid pro quo—even just access—is technically if not legally guilty of accepting a bribe); and most of the justice system prosecutors who place winning convictions over being honest brokers of the law would be, or should be, in prison as well. Concealing evidence that would exonerate an accused person is tantamount to stealing liberty from that person. Likewise, manufacturing evidence to convict a person the prosecutor—or the police—"knows in their guts" is guilty but can't prove, is equally aberrant and simply cannot be tolerated in a democratic society—even if the person being framed needs to be in prison.

Griffin was a career criminal. First offense—May 6, 1974. Griffin was sentenced to the Missouri Dept. of Corrections for three years for two burglaries. Released after one year. Nov. 10, 1975—sentenced to 3 years probation for stealing over $50,000. May 11, 1977—convicted of second degree burglary. Six months probation. Third offense—May 19, 1977. Convicted of theft of less than $50,000. Sentenced to 30 days. His probation on the 1975 charge was revoked on June 4, 1977—when he was convicted of felony possession of a controlled substance and assault. He served a three year sentence for the felony possession concurrent with the 1975 sentence. That, of course, is like getting two birds with one stone—for the criminal.

Two years later Griffin was back on the street—or, rather, he was back in court. On April 11, 1979 he was sentenced to 10 years for armed robbery and felony possession of a controlled substance. He was simultaneously sentenced to 5 years for second degree burglary and for carrying a concealed weapon. All sentences were concurrent. Griffin should have served ten years. If he had, he'd probably still be alive. Instead, he was out in one.

On June 26, 1980 three African-American males gunned down Quintin Moss at 4:25 p.m. at the intersection of Sarah Avenue and Olive Street in a driveby shooting. Another black man, Wallace Conners, standing about 75 feet away, was struck by a bullet, but lived.

One year to the day later, on June 26, 1981—based on the testimony of one "eyewitness"—Larry Griffin was convicted of first degree murder and sentenced to die by lethal injection. The only problem is, the police's eyewitness was not at the intersection of Sarah Avenue and Olive Street at 4:25 p.m. on June 26, 1980. Neither was Larry Griffin. He was helping a family friend sell a canoe on the afternoon of June 26. However, according to the prosecution, Griffin's alibi fell apart on the stand when the prosecution was able to show that the date on the check for the purchase of the boat was June 25. Griffin's family suggests the buyer accidentally dated the check for the 25th instead of the 26th. All of the parties involved in the sale of the canoe remembered the transaction taking place on June 26.

Let's look at the "integrity" of the evidence used by the State of Missouri, which used a police informant to convict Larry Griffin. First, the 1968 Chevrolet Impala that was both described and identified as the gunman's car was found later that night. Inside were the murder weapons—one handgun and one rifle. Also found in the vehicle owned by a drug dealers named Ronnie Thomas, was a traffic ticket made out to Reginald Griffin, the 19-year old nephew of Larry Griffin. Moss, the victim, had purportedly killed the Reggie's father, Dennis Griffin—Larry's brother. The prosecution would argue, at Larry Griffin's trial, that Larry killed Moss to revenge his brother's death. Somehow the prosecutor couldn't find a motive for Reggie Griffin to kill Moss—even though it was his father that was killed by the drug-dealing gang hit man.

Thomas,

Reggie Griffin and Ronnie Parker denied any knowledge

of the shooting. All three are now serving life without parole sentences—but

not for killing Moss.  According

to Gordon Ankney, the prosecutor who got the Larry Griffin

conviction, he didn't "feel comfortable" enough with the

evidence to prosecute Reggie Griffin and Thomas. "We

didn't have any witnesses to identify them," he said. "That's

what makes no sense about the [new] report [that names as suspects Reggie

Griffin, now 44; Thomas, now 50; and Ronnie Parker,

now 54 as the killers of Quintin Moss]. All three are

currently serving life sentences for murder."

According

to Gordon Ankney, the prosecutor who got the Larry Griffin

conviction, he didn't "feel comfortable" enough with the

evidence to prosecute Reggie Griffin and Thomas. "We

didn't have any witnesses to identify them," he said. "That's

what makes no sense about the [new] report [that names as suspects Reggie

Griffin, now 44; Thomas, now 50; and Ronnie Parker,

now 54 as the killers of Quintin Moss]. All three are

currently serving life sentences for murder."

Ankney claims there were no witnesses to the driveby except police informant Robert Fitzgerald—who claimed that his car broke down at the intersection of Sarah and Olive earlier that afternoon and that he and a friend and his 4-year old daughter were trying to get the car started when the shooting occurred. Fitzgerald, then 36, said he was 20 feet away from the assailant's car when the shooting started and not only did he recognize Larry Griffin as one of the shooters, he quickly memorized the license plate—JPP 203—while shots were being fired at Moss. According to his own testimony, Fitzgerald was then forced to shield the 4-year old with his own body to keep her from being struck by flying bullets. Quite an amazing guy. Ankney saw nothing wrong with Superman's testimony even though no where in the police report from the scene was there a license number for the shooter's car. The prosecutor's office didn't waste their time interviewing any of the other witnesses who Ankney claims did not exist. Instead, he chose to believe the one witness who was never there. (Had the prosecutor's office taken the time to interview any of the other witnesses, it would have realized that not only was Fitzgerald was not there, neither was Larry Griffin.)

According to everyone who was there, there were no white people anywhere near the corner of Sarah and Olive around 4:30 p.m. on June 26, 1980. Even St. Louis patrolman Michael Ruggeri—the first police officer to respond to the shooting—said there was no white man there. "He might have been down the block," he said recently,. "He might have been across the street. He may have been—you know...I don't know where he was, but he wasn't there."

It appears much more likely now, in hindsight, that someone Ruggeri does not want to identify may have suggested to him that the reason he didn't see Fitzgerald was because the good Samaritan was trying to give Moss—who had died almost instantly—medical attention (even though first aid generally doesn't help people who are dead), and that was probably why Ruggeri didn't "see him." Unfortunately, when Ruggeri testified at the trial of Larry Griffin, that fabrication became all the corroboration the prosecution needed to confirm Fitzgerald's testimony. Ruggeri put him at the scene even though he now acknowledges that Fitzgerald was not there.

Wallace Conners (now 52), was interviewed by the police at the hospital where he was being treated for a gunshot wound in his right buttocks. Remember, he was the only witness Ruggeri interviewed at the scene. It was Conners who described—and later identified—the Chevy Impala. Within 30 minutes of the shooting, the police were showing Conners a photo of Larry Griffin and asking if he was the shooter. Conners said he was not. Conners was never called as a witness in the shooting. In fact, shortly after he was released from the hospital, Conners left St. Louis. "Fitzgerald wasn't there when it happened," Conners told reporters last week when they found him. "If he had been, he would have been shot just like everybody else."

When he was contacted by St. Louis prosecutor Jennifer Joyce and questioned about Fitzgerald, Conners was clear in his mind that there was no white man at that intersection. The Stroll was an all-black neighborhood. A white person would have stood out like a sore thumb. Patricia Moss Mason, the sister of Quintin Moss, told investigators that she watched the shooting of her brother from a nearby window. There was no white man anywhere around the crime scene. Walter Moss, Quinton's brother, contacted the prosecutor's office several times between the time of the shooting and the conviction of Larry Griffin to tell them his sister had witnessed the shooting. Moss and his sister were ignored by the St. Louis prosecutor's office. No one called. No one took her statement. The prosecutor, Moss said, had the attitude that they didn't need him because they knew everything they needed to know to convict Griffin. It seemed to Moss and Conners that the authorities were more interested in convicting Griffin than they were at getting at the truth. The question is, why?

The police had Thomas's car. Evidence found inside the car tied both Thomas and Reggie Griffin to the car the night of the shooting. Parker was seen with Thomas and Griffin that day. A forensic examination of the Impala would probably have tied all three of them to the crime. Yet, the police were content to let them go and charge Larry Griffin.

While the State of Missouri will view this as a case of nothing more sinister than overzealous prosecution, someone in the St. Louis police department wanted Larry Griffin for this crime. They wanted him bad enough to fabricate an eye witness. Whomever brought Fitzgerald forward as the sole eyewitness of the shooting at the corner of Sarah and Olive on June 26, 1980 needs to be charged with first degree manslaughter in the wrongful death of Larry Griffin.

Fitzgerald, who was 36 at the time of the shooting, had been serving time for heroin possession, auto theft, armed robbery and possession of burglary tools. He was also facing four charges of credit card fraud. On June 26, 1980 Robert Fitzgerald—whom logic suggests would have been in police custody—was supposedly staying in a St. Louis motel under the federal witness protection program waiting to testify against a former associate who were about to stand trial for the murder of a Boston police officer. Yet at 4:30 that day, the prosecution was asking the jury to believe that Fitzgerald—who still had unserved prison time in front of him—was driving around St. Louis without a police escort. The day Griffin was convicted, Fitzgerald was released from custody by St. Louis County authorities for time served.

Interestingly,

five months later Fitzgerald testified against his former crony

in the death of the Boston cop. The jury flatly rejected Fitzgerald's

testimony as bogus and acquitted the defendant.  Too

bad the St. Louis jury that tried Larry Griffin for the crime

very likely committed by his brother and two acquaintances wasn't as

smart.

Too

bad the St. Louis jury that tried Larry Griffin for the crime

very likely committed by his brother and two acquaintances wasn't as

smart.

After his conviction and sentencing, Griffin's lawyer filed for a new trial on Aug. 7, 1981. The motion was denied. Four days later a notice of appeal was filed. The Missouri Supreme Court affirmed Griffin's conviction on Dec. 20, 1983, confirming that they believed he had received a fair trial. On Oct. 1, 1984 the US Supreme Court denied certiorari. They believed he had a fair trial, too. On Nov. 16, 1984 Griffin's lawyer filed a Rule 27.26 motion for post-conviction relief in the Circuit Court of St. Louis City. On Feb. 23, 1987 the motion was denied. On Feb. 15, 1988 the Missouri Court of Appeals affirmed the denial of post-conviction relief. On June 3, Griffin filed a petition for writ of habeas corpus in the US District Court for the Eastern District of Missouri. It was denied on July 16, 1990. That decision was appealed to the US Court of Appeals for the 8th Circuit and was rejected on Oct. 11, 1991. Griffin, an innocent man, was running out of options—and time.

On July 16, 1992 Griffin got his first break. The 8th Circuit remanded the case back to the District Court for further proceedings. On Oct. 6, 1993 the District Court conducted an evidentiary hearing. The hearing concluded on Oct. 25 when Griffin's petition for a writ of habeas corpus was denied. The case went back to the 8th Circuit, which again remanded it back to the District Court which, again, denied the writ. This time, the 8th Circuit affirmed the District Court's denial.

Time had pretty much run out for Griffin. On May 15, 1995 the US Supreme Court denied certiorari. The struggle had reached its end.

Griffin didn't believe it. One of the last public comments made by Larry Griffin went to a St. Louis Post-Dispatch reporter. "I suspect my life will end soon if the State should have its way," Griffin wrote. "I am no angel, but nor do I deserve to lose my life for a murder I did not commit." Griffin was executed on June 21, 1995 by lethal injection. While he was very likely guilty of many crimes for which he was never punished, Larry Griffin was innocent of the crime for which the State of Missouri took his life.

When the State screws up and executes the wrong person, how do they fix it? How does the State restore to Larry Griffin the life they took from him? At times we believe the States thinks it is God since many of the bureaucrats within the system believe the State possesses the power of life and death. In reality, it has only the power of death. it can't correct its mistakes when it screws up.

It is likely that the Griffin case will be used as a moratorium on the death penalty. It should not be. In the past, death penalty opponents have only been able to argue the possibility that an innocent person could be executed, not that one had been. Over the last two decades approximately 75 condemned men on death row have been exonerated by DNA testing, which raises the question of how many innocent men were executed prior to the advent of deoxyribonucleic acid testing to compare the double helix genetic code of the accused with any trace genetic material found at the crime scene. After all, we didn't just start locking up innocent men in the last couple of years.

That's why the anti-death penalty movement exists. What happens when you execute an innocent man? You can't give him back his life when you discover, after the execution, that he was innocent of the crime for which he was put to death. The solution, however, is not to abolish the death penalty since, if used properly, the death penalty can serve as a major deterrent to capital offenses. The solution is to make sure an innocent person is never executed again. Peer review—honest peer review—will eliminate the possibility of executing an innocent man or woman in the future.

Peer Review

Those opposed to peer review will argue that, on top of a costly trial—some of which run into the millions of dollars—peer review is a needless added expense that merely duplicates the investigative work done by the State just prior to the trial. However, in the case of Larry Griffin had an unbiased third party interviewed the witnesses they would have learned [a] none of them saw Larry Griffin in the Chevy Impala that gunned down Quintin Moss, and [b] none of them saw a white man anywhere near the crime scene, meaning the prosecution's witness, who was given his freedom by St. Louis County officials for his testimony, was a ringer. If all of the real witnesses—those interviewed at the crime scene and those who came forward within the days to follow—contradicted not only the testimony of the one state witness but the fact that the witness was actually not a witness to anything, [c] why did the county prosecutor, Gordon Ankney, accept the testimony of a man who should have been a discredited witness, and [d] why did he choose not to file charges against three men which the evidence put at the scene of the crime? Independent peer review by a board of investigators from outside St. Louis County might not have solved the case, but it would have raised enough questions that Griffin would have been granted a new trial—outside of St. Louis County.

Since Griffin was not arrested until April 4, 1981—almost a year after the crime was committed, there would have been no forensics material to test, nor was there any DNA material. The clothing worn not only by Griffin but by his nephew, Thomas and Parker would have been washed countless times in the ten months since the crime was committed, or discarded and not available for "testing" a year later. The fact that the police showed Connors a mugshot of Larry Griffin and not Reggie Griffin, Thomas and Parker at the hospital where he was being treated for his gunshot wound within a half hour of the shooting suggests that whomever was in charge of the Moss investigation had already decided that Larry Griffin was guilty. As is far too often the case, shoddy police work and hasty judgments combined with what we now know was the fabrication of evidence to "tie up the loose ends" led to the arrest and conviction of the wrong person.

But that doesn't excuse Ankney who, as the prosecutor, had a responsibility to make sure every possible witness had been interviewed and any discrepancies between each witnesses' version were resolved before the trial, and that the names of conflicting witnesses were provided to the attorney defending the accused. Wayne Moss, Wallace Conners and Patricia Moss Mason were never called to testify—for either side. Yet Conners not only has a clear recollection that Larry Griffin was not in the Chevy Impala, he put Thomas, Reggie Griffin and Parker in the Impala at 4:25 p.m. on June 26, 1980 at the intersection of Sarah Avenue and Olive Street. This information was available to the St. Louis police and the St. Louis prosecutor at the time of the killing. Why did they choose to ignore it? For whatever reason, the police had already decided, before the investigation began, that Larry Griffin was the killer. Peer review by an unbiased third party would have revealed that in 1981.

If peer review of the police investigation did not shed any new light, the next step in the peer review process would be to examine the professional conduct of both the prosecutor and the defense attorney to make certain each acted properly and that evidence that may have exonerated the accused—or at least raised questions about his or her guilt or innocence—was not concealed by the prosecution.

At the same time, the judicial peer review panel (that would be comprised of three judges from other jurisdictions, three prosecutors and three competent defense attorneys, all from different jurisdictions) would evaluate the competency of the defense offered by the accused's lawyer. The panel would also review the judge's conduct during the trial and the evidentiary rules put into place to admit or block certain pieces of evidence and testimony. Because this would be a peer review and not a trial, the panel would be allowed to examine any evidence not admitted to determine if, by the admission of that evidence, a different verdict would likely have been reached by the jury—and whether the judge erred by not admitting it. The findings of the peer review board would be automatically submitted to the federal appellate court of jurisdiction for a ruling. If the peer review uncovered exculpatory evidence that was not heard by the jury—even if it was barred by the judge—the death sentence would be permanently vacated. If the collection of evidence is found to be suspect, or a trial error is uncovered, a new trial in another jurisdiction would be ordered by the appellate court.

Under our current system of justice, appeals must be based on the evidence offered at the original trial, or on new evidence—such as DNA—that was not available at the time of the original trial (unless the defense attorney raises an objection to the admission of prejudicial evidence by the prosecution, or the refusal of the judge to admit evidence he requires to prove the innocence of his or her client). The defense attorney cannot reexamine the evidence and second guess the magistrate on appeal. In other words, the appellate court will not let the defense retry the case on appeal. The peer review system would obligate the appellate court to do that very thing if the peer review board found irregularities that suggested the accused did not receive a fair, impartial and most of all, honest, trial.

If such a peer review system existed, and everyone from the investigative officers to the judges would know that their professional conduct was going to be examined under a microscope at the end of the judicial journey, it is likely that rushes to judgment would be greatly reduced and officers of the court would cross all the "t's" and dot all of the "i's" before taking a case to the jury and demanding the death penalty for those accused of capital offenses. In the long run, it would save each State countless billions of dollars from the countless appeals filed by every condemned inmate in our penal system—and by eliminating the cost incurred by the State to house condemned killers for 10 to 20 years or more while the appeals process plays out. Using the peer review system with an unbiased review board that includes death penalty opponents, the death sentences would be carried out within 30 to 90 days of the ruling of the appellate court without exception. The savings to the States would be astronomical, and the families of the victims would see justice done swiftly.

Everyone involved in the justice system who deal with other people's lives, must be accountable to someone else for their actions. Today, that is not the case. Tomorrow, because of Larry Griffin, it needs to be.

Once again, you have my two cents worth on this subject.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.