News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

Walmart

wins in the US Supreme Court. Largest

class action lawsuit in history decertified. Those

who expected something for nothing...and a whole

big bunch of lawyers, mourn the decision.

The lawsuit, Dukes v Walmart, still exists since it has not

yet had its day in court. It's just that as of today, it's no longer

a class action that represents 1.5 million women who never filed

a lawsuit against the largest retail chain in the world. Today it

is what it should have been all along: a frivolous lawsuit filed

by one disgruntled Walmart greeter, Betty Dukes, against

her employer for failing to promote her. Dukes, who still

works at the Walmart store in Pittsburg, California where lawyers

initiated her famous but totally unmerited lawsuit, was the lead

plaintiff in what was, until Monday, June 20, the largest class

action lawsuit in history.

Before

looking at the landmark class action case that would have made multimillionaires

out of all of the lawyers who have managed since 2001 to attach

themselves to the case, its important to look at the cast of plaintiffs

in this made-for-TV drama since that's what tells you why this lawsuit

lost its class status. Let's begin with Betty Dukes.

Before

looking at the landmark class action case that would have made multimillionaires

out of all of the lawyers who have managed since 2001 to attach

themselves to the case, its important to look at the cast of plaintiffs

in this made-for-TV drama since that's what tells you why this lawsuit

lost its class status. Let's begin with Betty Dukes.

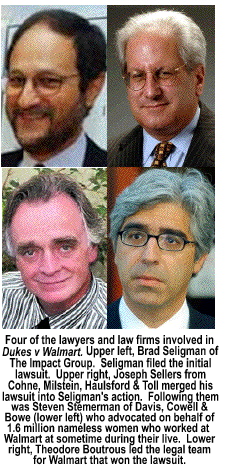

The New Yorker magazine described the lawsuit which used Betty Dukes' name as the centerpiece of oppressed womanhood as a "David and Goliath story." In reality, like all class action lawsuits, it was a legal obfuscation perpetuated, first by her lawyer, Brad Seligman, and then by Joseph Sellers, Stephen Tinkler, Debra Gardner and Steve Stemenman because none of the plaintiffs, on their own, had a case.

Betty Dukes, a lay preacher who was hired as a permanent part-time Walmart cashier in the company's Pittsburg, California store in 1994, sued in 2001 because she was denied a management promotion she was not qualified by education or work experience to claim. As is common practice in all companies in the United States, new employees serve a 90-day "at will" probationary periods during which time they are evaluated by management to determine if they have the basic work skills needed to continue employment.

At the

end of 90 days, Dukes received the same 25¢ per hour

raise all new employees receive at the end of their probationary

period—if their employment is continued. Her lawyers argued

in their brief that because Dukes told her manager that she

wanted to advance her career, and was told that she had to complete

her first 90 days before talking about the future, that some sort

of verbal promise was made between the manager and Dukes.

In point of fact, her boss was simply telling her she had to get

through her probationary period before she would be considered a

Walmart associate.  His

comment, even though it was construed as such by Dukes and

her lawyers, was not a "pledge" to fast track her into

Walmart's management program it was a statement that it was

premature for her to be talking about career advancement since it

was unclear at that point if she would still be employed after 90

days.

His

comment, even though it was construed as such by Dukes and

her lawyers, was not a "pledge" to fast track her into

Walmart's management program it was a statement that it was

premature for her to be talking about career advancement since it

was unclear at that point if she would still be employed after 90

days.

Dukes was elevated to an in-store position of Customer Service Manager in 1997, a job that required only the approval of her store manager (unlike senior store management positions which require corporate-level approval). Dukes noted in an interview that after becoming Customer Service Manager, every promotion beyond that point was much harder—and the hurdles much more frustrating. The reason, of course, is that corporate management positions are not based on tenure. They are based on a combination of education, work experience and, more times than not, having someone at corporate throw your name in the hat—or championing your promotion over someone else once your name is being considered for a career step-up promotion.

(As a former discount department store industry store manager and corporate-level retail industry executive in the 1970s and 1980s, my elevation from Assistant Store Manager to Store Manager was the result of being recommended by company's Vice President of Security. [It didn't hurt that I was hired by the Chairman of the Board of that retail chain who drove 90 miles to personally offer me a job.] Luck always plays a role in success. But you have to have the right work skills and background to get through the door to the ground floor of opportunity.)

In Dukes' case, from the myriad of articles I have researched and read over the last decade going back to her original 2001 lawsuit (which I wrote about extensively at the time) I know there was an "evolution" in the logic why she was demoted from Customer Service Manager in 1998 and is now a Walmart greeter. (I suspect the evolution of logic came, in part, from her advocates in the blogsphere who know the Goliaths always trample the Davids in the real world—thus, the Betty Dukes of the world are entitled to their Cinderella dream that because they are available for promotion, they should be promoted.

In 1998,

Dukes made a colossal blunder. Going on her break one day,

Dukes needed some change for the vending machine in the employee

lunch room. Although it was a violation of company policy to do

so—her "everyone does it" excuse notwithstanding,

Dukes had one of the cashiers open her register to make change

for her. She was demoted with a loss of 37¢ per hour due to

the job classification change. A few months later, she was reprimanded

for returning late from her breaks. In her lawsuit, Dukes

claimed this was the reason for her demotion.  Why?

Because male employees at the Pittsburg store were also reprimanded

for returning late from their breaks, but they were not demoted

and docked 37¢ an hour with a job description reclassification.

Likewise, none of them asked a cashier to open their cash drawer

to make change for them—the reason for the job demotion.

Why?

Because male employees at the Pittsburg store were also reprimanded

for returning late from their breaks, but they were not demoted

and docked 37¢ an hour with a job description reclassification.

Likewise, none of them asked a cashier to open their cash drawer

to make change for them—the reason for the job demotion.

Her lawyer's advanced the logic that the 25¢ end-of-probationary-period raise somehow constituted a promise by Walmart to more than simply provide Dukes with employment, was flawed since Walmart's policy is no different than that of any other retail company's hiring practices.

Conversely, when Dukes was demoted for violating Walmart security rules by asking a cashier to make change for her from the register, the "humiliation" Dukes said she endured by having her pay decreased 37¢ an hour was self-inflicted. It was not based on the fact that she was a woman. It was based on the fact that the job to which she was reassigned paid 37¢ an hour less than Customer Service Manager. Dukes could have been fired for the infraction. Her boss made a more benevolent choice. At the end of the day, she still had a job. It was different job than she had when she went to work that morning, but she was still employed as a cashier.

When Dukes became eligible for promotion after the most recent disciplinary action (she was ineligible for one year), she noted in her lawsuit, two men who were hired after her were promoted despite their "...lack of experience and seniority." In the world of labor unions where mediocrity is always rewarded, promotions are based on Dukes criteria—seniority. Not merit.

The far leftwing Alliance for Justice, which championed the class action lawsuit as hard as it fought US District Court Judge Robert Bork's nomination to the US Supreme Court in 1987, noted on their Justice Watch blog that after Dukes discussed her concerns about getting promoted in Walmart's Pittsburg store, store managers retaliated against her by penalizing her for returning late from her breaks. Justice Watch, a pro-union social progressive, anti-free enterprise advocacy group, apparently knows nothing about the management hierarchy of the retail industry, particularly that of the large national chains. Store management in national chains have absolute control over the hiring, firing and instore promotions of hourly employees. Every store manager and every district manager understands that hourly employees—particularly those who are undereducated and destined by their station in life to work dead-end, minimum wage jobs that present no real advancement opportunities—will always approach the "big boss" when he or she visits their store every week or two, believing that the elusive promotion does not require more education and experience than they possess.

People like Nan Aron, a former trial attorney who serves as president of Alliance for Justice, cut her social justice teeth as a staff attorney for the National Prison Project and the Student Action Campaign. Like all social progressives Aron believes Dukes should have been promoted for three reasons. First, even through she was a part-time employee,. she had been with Walmart 17 years. That was reason enough for Aron to elevate a part-time greeter (the job she now holds) into store management. Second, Dukes is a woman and, third, she is a minority—which means she is entitled. Most of the women claimed they were denied the opportunity to vie for store management positions because the jobs were never posted for store employees to apply for them.

Which was the essence of Dukes v Walmart. Unqualified and, in most cases, barely employable people—both male and female—find semi-permanent berths in the part-time job market. In my retail experience from years ago there were no part-time workers on anyone's radar screen for promotion. On June .8, 2001 Betty Dukes, Patricia Surgeson, Cleo Page, Deborah Gunter, Karen Williamson, Christine Kwapnowski and Edith Arana became part of a lawsuit against Walmart. Later Stephanie Odle and Sandra Stevenson's lawsuit against Walmart was joined to Dukes v Walmart.

Karen

Williamson started with Walmart in 1995. Like Dukes,

she expressed an interest in being promoted but, she claimed, she

was denied the chance. She applied for a Department Manager's job.

The position was given to a male employee with less seniority. Management

positions in any national retail chain are never based on seniority.

They are based on the quality of the employee's work skills.  Christiine

Kwapnowski was a Sam's Club employee since 1986. When

Dukes v Walmart was certified as a class action on June 22,

2004, Kwapnowski had been working for the Bentonville, Arkansas

retailer for 18 years. After the lawsuit was certified as a class,

Kwapnowski was promoted to Assistant Store Manager. The promotion

did not deter her zeal to pursue her allegations of discrimination.

Christiine

Kwapnowski was a Sam's Club employee since 1986. When

Dukes v Walmart was certified as a class action on June 22,

2004, Kwapnowski had been working for the Bentonville, Arkansas

retailer for 18 years. After the lawsuit was certified as a class,

Kwapnowski was promoted to Assistant Store Manager. The promotion

did not deter her zeal to pursue her allegations of discrimination.

Edith

Arana worked in Walmart's Duarte, California store for

six years. Arana worked in retail most of her life. Like

many of the other Walmart co-defendants, Arana believed that

time spent as a retail clerk qualified her to assume the profit

and loss status of a 65 thousand to 100 thousand square foot store

employing 50 to 100 people.  Arana

became convinced that, since she spent her life in retail, the reason

she did not advance into management had nothing to do with the fact

that she lacked the skillset needed to move into management. She

blamed her lack of upward mobility on the fact that she was African

American. To her, she was passed over for promotion not because

she lacked the qualifications, but because she was a minority. But

most of all, she was convinced that she was passed over for promotion

because of Walmart's policy of not posting announcements

for Assistant Store Manager positions. Because in her mind she believed

she was denied the right to compete for the promotions.

Arana

became convinced that, since she spent her life in retail, the reason

she did not advance into management had nothing to do with the fact

that she lacked the skillset needed to move into management. She

blamed her lack of upward mobility on the fact that she was African

American. To her, she was passed over for promotion not because

she lacked the qualifications, but because she was a minority. But

most of all, she was convinced that she was passed over for promotion

because of Walmart's policy of not posting announcements

for Assistant Store Manager positions. Because in her mind she believed

she was denied the right to compete for the promotions.

Again, in all national chains, positions of store manager and assistant store manager are never posted since those positions are not filled by the store management team. Store manager and assistant store manager jobs are career positions that result from corporate hirings. In most retail chains, those decisions are made by the Vice President of Store Operations. In Bentonville, the mechanics of populating stores with managers falls on Walmart's Vice President of People (Human Resources), but the decisons of who those managers will be falls on on the senior operations management who selects new hires from the pool of applicants who answer their career management ads in trade publications are large circulation daily newspapers.

Oh, by the way. Walmart's Vice President of People (i.e., their Human Resounces administrator) is a woman. Gisel Ruiz, an 18-year Walmart employee, began her career with Walmart as a store manager trainee (one of those non-posted jobs that the codefendants believe are not posted to keep women from getting them). Ruiz holds a Bachelor of Science degree in Marketing from Santa Clara University where she also completed the Retail Management Institute program. Ruiz has held a variety of management roles in store operations, labor relations and human resources. In 2006 Ruiz was promoted to vice president, regional general manager in the field operations division and was personally responsible for 150 Walmart stores in western Texas and New Mexico. In 2008 she was elevated to Senior Vice President of Walmart People, and received Walmart's Leadership Award. In 2009 Hispanic Business Magazine picked Ruiz as one of the top 25 business women of the year.

While the Walmart class action lawsuit was initiated by Brad Seligman of The Impact Group, Joseph Sellers of Cohen, Milstein, Haulsford & Toll stepped in second and spent $7 million of its own money to do the leg work and pore through thousands of pages of employment documents searching for the latchpin that would lock 1.6 million current and former Walmart employees together in a common cause action that would result in a multi-billion dollar They didn't spend that money because they were concerned that women and minorities were not gettng a fair shake from Walmart. They did it because they expected to make a healthy profit—for their firm—from their investment.

According to Seligman in 2004 when the federal court in San Francisco certified Dukes v Walmart as a class action, it was not about money. For that reason, when Duke v Walmart was certified as a class action, Seligman met with Walmart lawyers in a dingy conference room in Seligman's Berkeley, California office whose two windows look out at blank walls. The conference table was scratched and shop worn and the carpet was worn and dull. "I wanted them to see this wasn't about money. That this case wasn't just about money. We brought the action," Seligman said, "because Walmart needs to change." It sounded good when the Seattle Times printed the story. But the reality is, it is just about the money.

Seligman can talk about forcing Walmart to change all he wants, but the long and short of it is, class action lawsuits are the most lucrative legal actions—especially for the lawyers who chase them. If The Impact Group was not going to make a penny from the action if the plaintiffs prevailed, Seligman, The Impact Group, Cohen, Milstein, Haulsford & Toll, The Public Justice Center, Davis, Cowell & Bowe and several other public interest groups who joined the suit, would not have joined the suit. Law suits are a "for profit" business. No profit. No lawsuit.

Two of the plaintiffs in Dukes v Walmart, Betty Dukes and Christine Kwapnowski have made it clear their lawyers have not given up the fight against Walmart despite the high court's decison. The Supreme Court's decision only decertified the class action in its current form. It did not deal with the specifics of the allegations and, thus, each individual claimant can individually and collectively, still pursue satisfaction on the merits of their own actions. Most of them, of course, have no merit which is why their lawyers sought the class status in the first place.

Cohen, Milstein, Haulsford & Toll appears ready to break down Walmart's conjectured discrimination against women and minorities with a series of a small, manageable class action suits—one Walmart store at a time.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.