News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

(Part of the "Enemy Downtown" series)

ouston

financier and corporate raider Charles Hurwitz's problems

began with the collapse of a little known Texas thrift in 1988,

United Savings Association of Texas—only Hurwitz's

purported complicity in the collapse of the savings and loan

company never surfaced until about the time his company, MCO

Holdings (which changed its name in 1995 to Maxxam, Inc.)

assumed Pacific Lumber Company in 1986.

ouston

financier and corporate raider Charles Hurwitz's problems

began with the collapse of a little known Texas thrift in 1988,

United Savings Association of Texas—only Hurwitz's

purported complicity in the collapse of the savings and loan

company never surfaced until about the time his company, MCO

Holdings (which changed its name in 1995 to Maxxam, Inc.)

assumed Pacific Lumber Company in 1986.  Once

the Pacific Lumber buyout was complete Hurwitz's

problems began. But not from the US government— from environmentalists.

Once

the Pacific Lumber buyout was complete Hurwitz's

problems began. But not from the US government— from environmentalists.

One of Pacific Lumber's most valuable assets was a stand of 1,000-plus year old coastal redwood trees in Humboldt County—in a 6,000 acre tract of ancient redwoods in the 90,000 acre Headwaters' Forest know as the Headwaters Grove. Each of the 300 foot tall ancient giant redwoods have a commercial street value—as cut lumber—of at least $100,000. Hurwitz, who used junk bonds to finance his takeover of Pacific Lumber needed to liquidate some of the assets of the newly acquired company to pay down the debt.

Hurwitz became interested in Pacific Lumber when junk bond investment banker Drexel Burnham Lambert advised MCO that Pacific Lumber had made an overpriced offer to buy back its own stock in 1984, causing MCO to take a closer look at the company as a potential hostile takeover since Pacific was not interested in suitors. And the closer Hurwitz looked, the better Pacific Lumber looked. Finally, in October, 1985 he went after it, assuming control of the company in 1986.

Environmentalists feared Hurwitz

would clear-cut the Headwaters Grove of its ancient treasures

to pay for the takeover. In reality, Hurwitz already

planned to sell off specific assets of Pacific Lumber

to pay for the takeover—and the Headwaters Grove

was not part of his thinking. However, MCO Holdings,

which was extremely leveraged, still needed to generate a revenue

stream, and planned to clear-cut up to a thousand acres of Pacific

Lumber's expansive reserve of Douglas pines, spruce, coastal

redwoods and other timber species which the company owned.  Within

a matter of months, Hurwitz doubled Pacific Lumber's

relatively conservative lumber harvesting practices. Tthat convinced

the greens that a land-stripper had taken over the 117 year

old company.

Within

a matter of months, Hurwitz doubled Pacific Lumber's

relatively conservative lumber harvesting practices. Tthat convinced

the greens that a land-stripper had taken over the 117 year

old company.

Pacific Lumber was an institution in northern California, and had been since 1869. It was the largest employer in Humboldt County, owning around 194,000 acres of prime timberland worth billions of dollars at retail. Yet, it was not as profitable as it could have been, or should have been, due to environmentalists who did everything possible to hamstring logging operations for over a decade. The constant inference of Pacific's logging operation by radical green groups made Pacific Lumber "easy pickings" for any corporate raider. When Hurwitz took it over it wasn't long before green groups like Earth First!, the Sierra Club and Greenpeace were targeting Hurwitz, who became the "scorched earth" villain.

In January 1995, Humboldt environmentalist activist Robert Martel filled a lawsuit in US District Court against Maxxam, Industries seeking $1.6 billion to cover the losses suffered by Maxxam's bankrupt S&L, United Savings Association of Texas plus an additional $4.8 billion in punitive damages on behalf of the American taxpayers. Because Martel represented neither the government nor the depositors of United Savings, there was no legal basis for his filing. But, his lawsuit opened Pandora's box. When the federal court—which should never have accepted the action in the first placed—ruled against him, Martel appealed that court's decision to the 5th Circuit Court of Appeals. The appellate court not only rejected Martel's appeal, it ordered him to pay Maxxam's legal fees of more than $110,000, saying that Martel's case was "frivolous"

.jpg) In

August of 1995, FDIC Chairman Ricki Tigert-Helfer filed

the first of two "recovery" lawsuits in US District

Court in Houston. The action, FDIC v Hurwitz, sought

$250 million in damages—not from Maxxam (as MCO

Holding had been renamed)—but from Hurwitz personally.

When she filed her suit, Tigert-Helfer asked the Office

of Thrift Management to investigate Charles Hurwitz

and Maxxam for wrongdoing. In December, 1995 the Office

of Thrift Management filed 13 claims against the defendants

of its own lawsuit—against Hurwitz, Maxxam,

two other Maxxam companies: Federated Development

Company, United Financial Group (which was the parent

company of United Savings), and the former and current

directors of the S&L. The OTM sought $821 million

in damages. The FDIC and the OTM both alleged

that Hurwitz's business dealings with Drexel Burnham

Lambert contributed significantly to the thrift's failure

by not keeping it properly capitalized. They also alleged that

Hurwitz "raided" the assets of United Savings

to purchase Pacific Lumber, making Hurwitz personally

liable for the $1.6 billion the OTM claims United

Savings lost.

In

August of 1995, FDIC Chairman Ricki Tigert-Helfer filed

the first of two "recovery" lawsuits in US District

Court in Houston. The action, FDIC v Hurwitz, sought

$250 million in damages—not from Maxxam (as MCO

Holding had been renamed)—but from Hurwitz personally.

When she filed her suit, Tigert-Helfer asked the Office

of Thrift Management to investigate Charles Hurwitz

and Maxxam for wrongdoing. In December, 1995 the Office

of Thrift Management filed 13 claims against the defendants

of its own lawsuit—against Hurwitz, Maxxam,

two other Maxxam companies: Federated Development

Company, United Financial Group (which was the parent

company of United Savings), and the former and current

directors of the S&L. The OTM sought $821 million

in damages. The FDIC and the OTM both alleged

that Hurwitz's business dealings with Drexel Burnham

Lambert contributed significantly to the thrift's failure

by not keeping it properly capitalized. They also alleged that

Hurwitz "raided" the assets of United Savings

to purchase Pacific Lumber, making Hurwitz personally

liable for the $1.6 billion the OTM claims United

Savings lost.

From the time the dual actions

were filed by the FDIC and the OTM, Hurwitz's

lawyer, Richard Keeton, was approached by various environmental

groups suggesting that the government would entertain a "debt-for-trees"

swap. Hurwitz would get to walk away from the FDIC

and OTM charges if he agreed to allow the old stand of

300' tall redwoods in Headwaters Grove be deeded to the

US government. The government would make the Headwaters

redwoods part of the Six Rivers National Forest. In

the early 1990s, Howard Hughes' estate engaged in a "debt

for nature" swap when the estate traded some wetlands near

the Los Angeles Airport to settle a tax bill owed the State

of California. Several third world countries swapped land that

US environmentalists thought should be protected for the debt

they owed the United States.  Bolivia

traded tropical forests to clear their debt. Land swaps were

also done with the Philippines and several other nations as

well.

Bolivia

traded tropical forests to clear their debt. Land swaps were

also done with the Philippines and several other nations as

well.

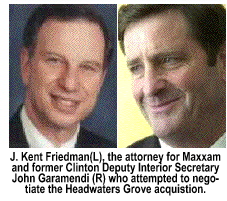

In February, 1997 Deputy Interior Secretary John Garamendi approached Maxxam to arrange for the acquisition of the Headwater Grove. Maxxam's general counsel, J. Kent Friedman, told the Clinton Administration official that Maxxam would consider selling the Headwater Grove to the Interior Department—but only on the condition that the government drop its FDIC lawsuit. "We want this case to go away," Friedman said.

Garamendi reported "...Hurwitz

brought that to the table numerous times," but he added,

he refused to intervene on Hurwitz's behalf, concluding

it would be inappropriate for the Interior Department to get

involved in the FDIC's business. Friedman said

Maxxam raised the issue about the FDIC case because

the action should never have been filed against Hurwitz who

had undergone a lengthy, politically-motivated and ultimately

unproved investigation by the Clinton Administration

and a federal agency that violated its own rules in bringing

the action.  Hurwitz

was not liable for the failure of United Savings because

neither he nor Maxxam had controlling interest in United

Financial—the holding company that had a minority interest

in United Savings—therefore neither Hurwitz

nor Maxxam had any legal authority to control the capital

levels at the thrift. At the time the Garamendi negotiations

were underway, the the Rose Foundation for Communities and

the Government and several other environmentalist groups

managed to convince a federal court that Pacific Lumber

and a neighboring lumbering camp, Elk River Timber Company,

had both violated the Endangered Species Act by logging

pristine forests that sheltered the spotted owl. The federal

court issued an injunction forbidding either Elk River Timber

or Pacific Lumber from harvesting their land. Nine

times the environmentalists filed suit in federal court. Nine

times the court issued injunctions forbidding the lumber companies

from cutting trees on their own land due to violations of the

Endangered Species Act.

Hurwitz

was not liable for the failure of United Savings because

neither he nor Maxxam had controlling interest in United

Financial—the holding company that had a minority interest

in United Savings—therefore neither Hurwitz

nor Maxxam had any legal authority to control the capital

levels at the thrift. At the time the Garamendi negotiations

were underway, the the Rose Foundation for Communities and

the Government and several other environmentalist groups

managed to convince a federal court that Pacific Lumber

and a neighboring lumbering camp, Elk River Timber Company,

had both violated the Endangered Species Act by logging

pristine forests that sheltered the spotted owl. The federal

court issued an injunction forbidding either Elk River Timber

or Pacific Lumber from harvesting their land. Nine

times the environmentalists filed suit in federal court. Nine

times the court issued injunctions forbidding the lumber companies

from cutting trees on their own land due to violations of the

Endangered Species Act.

(Author's note: While I did not find documents to support my belief that Hurwitz, Friedman and Keeton were very bluntly, off-the-record, advised that they might as well sell the Headwater Grove to the environmentalists and get something for their buck because it was unlikely that, anytime in the foreseeable future, they would be able to harvest any lumber from that area since the Headwaters Forest was home to the spotted owl.)

In 1999 Hurwitz caved in and sold 10,000 acres of Headwaters Forest land to the Department of the Interior for $480 million. The deal was brokered by Sen. Diane Feinstein to preserve the old growth giant coastlal redwoods. In 2002 the FDIC dropped its 250 million action against Hurwitz when the OTM settled their $821 million case under an agreement where Hurwitz paid $206 thousand, made no admissions of wrongdoing, and agreed not to discuss the suit or the settlement.

But in his settlement, Hurwitz never agreed not to file suit against the government. He immediately sued the FDIC, by asking US District Court Judge Lynn Hughes (the presiding judge in the government's case) to award him $72 million in damages to cover his costs to fight not only the FDIC charges, but the costs associated with fighting to keep the government from seizing his redwood trees—and fighting frivolous lawsuits from the Rose Foundation, the Sierra Club, Greenpeace, Earth First! and scores of other green groups who lined up to take their best shot at Maxxam in court while Maxxam and Hurwitz were distracted with the FDIC lawsuit.

Hurwitz, through his lawyers, claimed that the Clinton Administration's FDIC [a] improperly funded another government agency's investigative witch hunt against Maxxam on the same matter; and, [b] his suite alleged that the Clinton Administration used bogus lawsuits in an attempt to force him to surrender over a billion dollars worth of prime coastal redwood trees to settle bogus claims against him and his company.

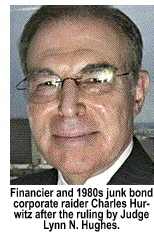

On

Tuesday, August 23, 2005 US District Court Judge Lynn Nettleton

Hughes issued his decision in FDIC v Hurwitz. It

was a scathing denunciation of a government, pressured by radical

environmentalist, to railroad an innocent man solely to steal

his land for special interest extremists. In what is now the

largest judgment against a federal agency ever awarded, Hughes

ordered the FDIC to pay Hurwitz $72.3 million.

In his 133-page decision, Hughes compared the federal

investigations of Hurwitz and Maxxam to "...secret

society of extortionists [that had practiced] craven submission

[when faced with pressure from the office of the Vice President

of the United States and] the green groups to cause him pain."

Hughes said Hurwitz was the victim of a vindictive

and politically-motivated federal agency. Hughes referred

to the ordeal Hurwitz was forced to endure in terms of

the Boston Tea Party, writing that "...Sam

Adams would say that somebody needs to dump the FDIC's

tea overboard." Hughes found, in his decision,

that the FDIC, in close concert with environmental groups,

sued Hurwitz to pressure him into a "debt-for-nature"

swap, in effect giving the government about a billion dollars

worth of trees in exchange for his supposed liability in the

failure of the United Savings Association of Texas.

On

Tuesday, August 23, 2005 US District Court Judge Lynn Nettleton

Hughes issued his decision in FDIC v Hurwitz. It

was a scathing denunciation of a government, pressured by radical

environmentalist, to railroad an innocent man solely to steal

his land for special interest extremists. In what is now the

largest judgment against a federal agency ever awarded, Hughes

ordered the FDIC to pay Hurwitz $72.3 million.

In his 133-page decision, Hughes compared the federal

investigations of Hurwitz and Maxxam to "...secret

society of extortionists [that had practiced] craven submission

[when faced with pressure from the office of the Vice President

of the United States and] the green groups to cause him pain."

Hughes said Hurwitz was the victim of a vindictive

and politically-motivated federal agency. Hughes referred

to the ordeal Hurwitz was forced to endure in terms of

the Boston Tea Party, writing that "...Sam

Adams would say that somebody needs to dump the FDIC's

tea overboard." Hughes found, in his decision,

that the FDIC, in close concert with environmental groups,

sued Hurwitz to pressure him into a "debt-for-nature"

swap, in effect giving the government about a billion dollars

worth of trees in exchange for his supposed liability in the

failure of the United Savings Association of Texas.

Paul Mason, a lobbyist and green activist for the Sierra Club summed up the view of the environmentalist movement when he noted that Judge Hughes had been hostile to the government's case against Hurwitz from the beginning. "To sate that the environmental community was steering the case," Mason told the media, "would strongly overstate the influence we had with the federal government."

The question is, who's telling the truth and who's lying? That's the part of the story you won't read in your local newspaper this evening—nor will you see it on Fox News. The chronology of events is not deeply hidden. A Google search will bring you most of the headlines. A little digging will give you the rest.

For the environmentalists to even suggest that not only were they not steering the Hurwitz case, but that they hadn't engineered it by persuading Vice President Al Gore, Interior Secretary Bruce Babbitt and other bureaucrats in the Clinton Administration to run interference for them in filing a lawsuit for damages against Maxxam that would force Hurwitz to agree to a "debt-for-nature" swap to alleviate his liability in the failure of United Savings Association of Texas—when the FDIC and the Clinton Justice Department knew he was not legally culpable for the failure of the S&L.

The radical environmentalist Earth First! hatched up the scheme for the FDIC to sue Hurwitz for the failure shortly after the co-presidency of Bill and Hillary Clinton descended on Washington, DC. In the usual fashion of the green extremists, Earth First! revealed its idea in a Spring, 1993 demonstration in front of the FDIC, demanding that the government take the old-growth redwoods that belonged to Pacific Lumber Company to settle any claims the FDIC should have with another Hurwitz company, the failed S&L, United Savings Association of Texas. Earth First! later insisted that their suggestion was politely offered at that time only because of the fear that Hurwitz would destroy the thousand year old trees that shielded the habitat of the spotted owl and other endangered species that lived in the Headwaters Forest in Humboldt County, California.

From that demonstration in 1993, both the Clinton Administration and Congress became acutely aware of the Headwaters Forest, Charles Hurwitz, United Savings Association of Texas and the implied liability of Hurwitz, whom the environmentalists claimed raided the assets of United Savings to leverage Pacific Lumber. Shortly after the demonstration Greenpeace, the Sierra Club Legal Defense Fund and the Rose Foundation for Community and the Government began to leverage Congress and Mr. Environment—Al Gore, Jr. The Rose Foundation and the Sierra Club became fixtures on Capitol Hill as they made their way from one Congressional and Senatorial office to another, and from the FDIC to the Office of Thrift Management, to the White House and Blair House, asking for legislation that would both implicate and exonerate Hurwitz by arranging a debt-for-trees swap in which the FDIC would exchange Hurwitz's liability in United Savings for 57,000 to 76,000 acres of Headwaters Forest which would be placed in the public trust.

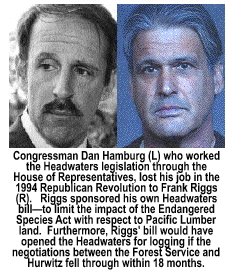

In

1994 Congressman Dan Hamburg [D-CA] introduced a bill

in the House of Representatives that would authorize the US

Forest Service to "negotiate" the transfer of the

Headwaters Forest under eminent domain to the US government

and make it part of the Six Rivers National Forest. The

bill passed in the House, but the Senate version of the bill,

introduced by Barbara Boxer [D-CA], never made it out

of committee and onto the Senate floor for a vote. When the

GOP Revolution in November of 1994 pushed the Democrats out

of all of the committee chairs in both the House and Senate,

the odds of enacting the Headwaters bill was greatly diminished.

The environmentalists reverted to the suggestion made by Earth

First!—convince the FDIC to file suit against

Hurwitz and then swap the Headwaters for a release

from liability on United Savings Association of Texas.

In

1994 Congressman Dan Hamburg [D-CA] introduced a bill

in the House of Representatives that would authorize the US

Forest Service to "negotiate" the transfer of the

Headwaters Forest under eminent domain to the US government

and make it part of the Six Rivers National Forest. The

bill passed in the House, but the Senate version of the bill,

introduced by Barbara Boxer [D-CA], never made it out

of committee and onto the Senate floor for a vote. When the

GOP Revolution in November of 1994 pushed the Democrats out

of all of the committee chairs in both the House and Senate,

the odds of enacting the Headwaters bill was greatly diminished.

The environmentalists reverted to the suggestion made by Earth

First!—convince the FDIC to file suit against

Hurwitz and then swap the Headwaters for a release

from liability on United Savings Association of Texas.

It was after the

defeat of The Hamburg-Boxer Act that Jill Ratner,

the lawyer activist head of the Rose Foundation intensified

her letter-writing campaign to entice FDIC Chairman Tigert-Helfer

to file a lawsuit against Hurwitz and then do a debt-for-trees

swap to settle the 1,000 year old redwood tree matter for all

time.  Ricki

Tigert-Helfer replied to Ratner that the FDIC

could not compel the defendants of any legal action to consider

a debt-for-nature swap since they might decide to use other

assets to satisfy their liability. It was obvious that the Bush-41

Administration clearly understood that minority shareholders

in companies—unless they are board members—have no

fiduciary control over the company, and thus can't be held liable

for any capitalization shortfalls of the company. And, it was

clear that, by the end of 1994 the Clinton Administration

believed they could arbitrarily assign "fault," and

in the Headwaters Forest matter, they had arbitrarily

decided that Charles Hurwitz was culpable in the United

Savings matter because the Sierra Club, Earth

First!, Greenpeace and the Rose Foundation

convinced the Clinton Administration—without any

actual evidence to support their position—that Hurwitz

had gutted United Savings Association and used what could

be construed as stolen assets to buy Pacific Lumber.

Thus, since ill-gotten gains paid for Pacific, it was

only fitting to the environmentalists calling for it, that Pacific

Lumber assets be used to satisfy the government's case against

Hurwitz.

Ricki

Tigert-Helfer replied to Ratner that the FDIC

could not compel the defendants of any legal action to consider

a debt-for-nature swap since they might decide to use other

assets to satisfy their liability. It was obvious that the Bush-41

Administration clearly understood that minority shareholders

in companies—unless they are board members—have no

fiduciary control over the company, and thus can't be held liable

for any capitalization shortfalls of the company. And, it was

clear that, by the end of 1994 the Clinton Administration

believed they could arbitrarily assign "fault," and

in the Headwaters Forest matter, they had arbitrarily

decided that Charles Hurwitz was culpable in the United

Savings matter because the Sierra Club, Earth

First!, Greenpeace and the Rose Foundation

convinced the Clinton Administration—without any

actual evidence to support their position—that Hurwitz

had gutted United Savings Association and used what could

be construed as stolen assets to buy Pacific Lumber.

Thus, since ill-gotten gains paid for Pacific, it was

only fitting to the environmentalists calling for it, that Pacific

Lumber assets be used to satisfy the government's case against

Hurwitz.

Ratner even raised the issue of debt-for-nature with Maxxam lawyers on several times. One one occasion, Maxxam spokesman Joshua Reiss dismissed Ratner's swap suggestion as a flawed premise since, he said, there is no debt to swap. Hurwitz, he told the media, had done nothing wrong. Since he did not possess controlling interest in United Savings, he had no legal authority to influence their policies.

John V. Thomas, associate general counsel for the FDIC wrote to a green activist, Larry Helbrook of Eleva, Wisconsin on August 23, 1994. Helbrook inquired about a possible debt-for-nature swap to protect the ancient Sequoia giants. Thomas responded, saying "We are mindful of the possibility that if Pacific Lumber's parent can be held liable for our losses, issues involving the redwood forests might be brought into play."

Shortly after she filed suit against Hurwitz, Tigert-Helfer wrote a letter to then US Congressman David E. Skaggs in which she said, in response to his question: "You may be assured that the government remains open to any appropriate settlement of this claim—including a debt-for-nature swap."

Throughout the last months of 1994 there was a flurry of high level meetings between the environmentalist lobbyists from Greenpeace, the Sierra Club, and the Rose Foundation, several liberal Congressmen and Senators, some high level Clinton Administration officials, and Vice President Al Gore who functioned as "control central" on the Hurwitz-Headwaters Forest matter. The high level meetings produced a compromise between the environmentalists and the Clinton Administration. The Al Gore emissary, Deputy Interior Secretary John Garamendi, was sent to Sacramento to meet with Hurwitz and his lawyers and negotiate the "surrender" of the Headwaters Forest.

For the environmentalists and former Clinton-Gore officials to claim they did not originate the debt-for-nature swap, or attempt to influence the filing of charges against Charles Hurwitz by the FDIC specifically to pressure him into settling the lawsuit by trading a billion dollars worth of redwood trees for a handful of spotted owls. Judge Lynn Hughes was right—the government lied. FDIC officials "...discarded the mantle of the American Republic for the clock of a secret society of extortionists. If the Vice President called, they responded. If a lobbyist called, they responded. They heeded every call but that of duty and honor."

FDIC spokesman David Barr said the agency will appeal the judgment. If the 5th Circuit Court knows how to do a Google search, without even holding a hearing, it will find enough material to uphold the opinion of Judge Hughes. If, on the other hand, the judges on the 5th Circuit believe that the Clinton-Gore Administration was an honest broker of justice, they will likely overrule one of the most intelligent decisions made by a US District Court Judge in 50 years.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.