News

Behind the Headlines

Two-Cents Worth

Video of the Week

News Blurbs

Articles

Testimony

Bible Questions

Internet Articles (2015)

Internet Articles (2014)

Internet

Articles (2013)

Internet Articles (2012)

Internet Articles (2011)

Internet Articles (2010)

Internet Articles

(2009)

Internet Articles (2008)

Internet Articles (2007)

Internet Articles (2006)

Internet Articles (2005)

Internet Articles (2004)

Internet Articles (2003)

Internet Articles (2002)

Internet Articles (2001)

ore

years ago than I care to remember—when I was just a young lad—parents

taught their children that the beat cop or the police officers who infrequently

cruised through the neighborhood, were people they could always trust.

You always felt safe when your next door neighbor was a cop. Throughout

the years, even dirty cops—those paid off by organized crime or by

local vice scumbags to ignore prostitution and gambling— were not

feared by the people they were hired to protect and serve. By the end

of the mob era, however, local police were generally viewed—in most

large communities—as a necessary evil. Law enforcement officers in

the nation's decaying urban centers and in the larger suburban areas of

the nation's growing regional megalopolises, were many times viewed as

brutal, corrupt vigilantes who were every bit as violent as those they

where charged with apprehending. Law-abiding citizens began to grow uncomfortable

around the men in blue and, many times, were suspicious and more than

a little mistrustful, of them.

ore

years ago than I care to remember—when I was just a young lad—parents

taught their children that the beat cop or the police officers who infrequently

cruised through the neighborhood, were people they could always trust.

You always felt safe when your next door neighbor was a cop. Throughout

the years, even dirty cops—those paid off by organized crime or by

local vice scumbags to ignore prostitution and gambling— were not

feared by the people they were hired to protect and serve. By the end

of the mob era, however, local police were generally viewed—in most

large communities—as a necessary evil. Law enforcement officers in

the nation's decaying urban centers and in the larger suburban areas of

the nation's growing regional megalopolises, were many times viewed as

brutal, corrupt vigilantes who were every bit as violent as those they

where charged with apprehending. Law-abiding citizens began to grow uncomfortable

around the men in blue and, many times, were suspicious and more than

a little mistrustful, of them.  For

that reason today, cops cluster with cops and most of their close relationships

are within the brotherhood of blue.

For

that reason today, cops cluster with cops and most of their close relationships

are within the brotherhood of blue.

For a few months in New York City after 9-11 America renewed its love affair with its police officers, but the headlines in the local newspapers brought them back to reality after a very brief honeymoon. America, with good reason, no longer trusts the law enforcement agencies responsible for keeping us safe and secure.

Increasingly today the police, the prosecutors, and the judges whose job it is supposed to be to make sure that justice is meted fairly and in an unbiased manner, are more dangerous and pose a bigger threat to the people of the United States than all of the killers, rapists, drug dealers and petty thugs who prowl the streets of America—because the people themselves have become the new profit center for the bureaucracy we call "law enforcement."

To aid the cities, counties

and States generate desperately needed revenues to meet growing budget

shortfalls created by shrinking tax revenues that have left many city,

county and State governments buried under a mountain of debt, activist

judges at both the State and federal levels have redefined who and what

is protected under the umbrella of the Bill of Rights by .jpg) ruling

that the protection we, as citizens, enjoy under the Constitution does

not necessarily extend to our property. Today, the bureaucracy is waging

a war of attrition against private property because property, separate

from the people who own it, has no Constitutional rights and, thus, can

be seized at will. To regain their property, the accused (who generally

is not arrested with their property) must be able to conclusively prove

how he or she received their property, which has already been seized.

This, of course, is precisely the reverse of the constitutional concept

of innocent until proven guilty.

ruling

that the protection we, as citizens, enjoy under the Constitution does

not necessarily extend to our property. Today, the bureaucracy is waging

a war of attrition against private property because property, separate

from the people who own it, has no Constitutional rights and, thus, can

be seized at will. To regain their property, the accused (who generally

is not arrested with their property) must be able to conclusively prove

how he or she received their property, which has already been seized.

This, of course, is precisely the reverse of the constitutional concept

of innocent until proven guilty.

In a rare instance where the

victim of aggressive police action actually won—two years, two months

and five days after the Drug Enforcement Agency [DEA] seized

$9,000 in cash from Willie Jones, a Nashville  landscaper,

US District Court Judge Thomas Wiseman ordered the government to

return his money. But, such reversals in the government's newest form

of revenue generation are extremely rare. Generally, the victims—law

abiding citizens—lose their property simply because they lack the

means to fight the government in court since normally, the seizure is

so complete that the defendant has nothing left with which to fight. And,

should they have "secret" savings, that money—when it surfaces

to pay for an attorney—is seized as well.

landscaper,

US District Court Judge Thomas Wiseman ordered the government to

return his money. But, such reversals in the government's newest form

of revenue generation are extremely rare. Generally, the victims—law

abiding citizens—lose their property simply because they lack the

means to fight the government in court since normally, the seizure is

so complete that the defendant has nothing left with which to fight. And,

should they have "secret" savings, that money—when it surfaces

to pay for an attorney—is seized as well.

In the case of Willie Jones, he was flying to Houston on February 27, 1991 to purchase plants for his landscaping business. He carried cash because experience had taught him that cash got him a better deal than either checks or credit cards. In addition, Jones was African American. Unknown to Jones, the DEA had previously struck a deal with ticket sellers not only with most of the nation's air carriers, but with Greyhound, Amtrak and even most major hotels to report to them when people pay for travel or accommodations with cash—especially large sums of cash. In Jones' case, he paid cash for his plane ticket. The American Airlines ticket clerk quickly reported Jones' cash purchase to a DEA agent nearby. The agent stopped Jones' and asked to see his identification. Then he asked if Jones' minded if the agent searched him.

Jones objected to being searched since he had done nothing to merit such action. The DEA agent told him that drug-sniffing dogs detected cocaine on the cash he paid for his air fare, and that alone justified the search. Finding the $9,000 Jones' was carrying—but no drugs or anything else illegal—they released him but "arrested" his money, telling him he would not be buying drugs with it. (A 1989 study found that 70% of all currency in circulation will likely have cocaine residue on it. That figure is much higher today. Now, well over 95% of all currency in circulation in the United States will contain trace signs of cocaine since using a rolled up dollar bill is the most common "straw" used for "sniffing" cocaine.)

Jones asked for a receipt for his money. The DEA agent gave him a receipt for an "undetermined" amount of money. Jones balked and insisted the agent physically count the money and give him an accurate receipt since he intended to get his money back. The agent refused, claiming that actually counting the money violated DEA policy. But you can bet he counted it very carefully because, under current seizure law, the agent who seized the assets receives 25% of the 80% retained by the DEA. The remaining 20% goes to the federal court system where it is placed in the judiciary's bank account to help defray the court's own operating expenses. There is an 80-20 split between the local, county, State or federal law enforcement agency that seizes the assets and the corresponding court that will deal with the "criminal"—which 80% of the time means the assets that were seized since charges are seldom filed against the victim over overaggressive police search and seizure tactics because there is generally no evidence that any crime has actually been committed. The assumption of guilt is now prevalent in law enforcement. In the judicial system, although it is incumbent upon the prosecution to prove guilt, it is equally obligatory for the defense to be able to prove innocence. In far too many instances across the nation, people are convicted of crimes ranging from simple burglary to murder not because the State proved they were guilty of the crime for which they were on trial, but because the defense was unable to prove the defendant was innocent of the charges.

When the Jones case finally showed up in US District Court Judge Wiseman's courtroom, the magistrate saw it for what it was. Highway—or rather, airport—robbery. And the crooks were the cops. Wiseman told the DEA, in court, that the reasons they offered for the seizure of Jones' money was "misleading," "unconvincing" and "inconsistent" and that the officer's behavior was casual and sarcastic. In his ruling he said: "Based on the credible evidence presented at the trial, Mr. Jones was unreasonably seized in violation of the 4th amendment...which prohibits illegal search and seizure of property." Wiseman called the Jones' seizure "...a forfeiture proceeding started in bad faith with wild allegations based on the hope that something would turn up to justify the search." Wiseman concluded that "...a growing chorus of courts are finding the evidence of narcotic-trained dogs alert to the currency is of extremely little weight," adding that, a study by Lee Hearn, chief toxicologist for the Dade County (Florida) Medical Examiner's Office found that 97% of the bills from around the country tested positive for cocaine. The DEA was forced to give Jones' back his $9.000.

Many times when "evidence" seizures occur—when an actual crime has been committed—the "crime" is a misdemeanor that is punishable by a small fine. Generally, the property seized by the police in misdemeanor arrests is worth hundreds if not a thousand times more than any fine that would be levied. (An example might be a "john" seeking the pleasures of a prostitute who may or may not be an undercover police officer. Since the "john" used his car to drive to the location where he tried to solicit paid sexual favors, the car—which can now be seized under current forfeiture laws—was used in the commission of a crime.) Whenever they can do so today, law enforcement officers "arrest" the property of "suspects" even if they don't have enough evidence to arrest the individual who owns the property. What is occurring is a legal form of theft for profit and personal gain by the police.

Most Americans—whether they are victims of overzealous cops on commission, or are guilty of misdemeanors that simply do not merit property forfeiture without due process—are not as lucky as Willie Jones. Forty-nine year old Ethel Hylton certainly wasn't. Her luggage was scratched by a drug-sniffing dog at Houston's Hobby Airport. Agents searched her luggage looking for drugs but found none. Then they strip-searched Ethel. Still, no drugs. But that didn't stop them from seizing the $39,110 in cash they found in the luggage. Even though Hylton was able to prove conclusively that the money came from a recent insurance settlement and her life savings from working as a hotel maid and as janitor in a hospital, that didn't cut any ice. She was never charged with a crime, because the DEA knew she had committed none. But they kept her money because the drug-sniffing dog had detected traces of cocaine on it. With every cent she possessed in the world gone and with absolutely no means to get more, no lawyer would take her case. And, since she was never charged with a crime, she was not entitled to a court appointed attorney. Without the means to fight, Hylton lost her retirement money.

Sam Thach, who was traveling by train from Fullerton, California to Boston was stopped and searched by the DEA after an Amtrak ticket agent fingered him. Thach appeared suspicious to the Amtrak ticket agent for two reasons. First, he paid cash for his ticket. Second, he refused to give the Amtrak agent his phone number. Unfortunately for Thach, the DEA stopped him in Albuquerque, New Mexico and searched him. He was carrying $147,000 in cash in his luggage. He had no drugs on him. Nor was there anything on or about him to suggest he had done, or intended to do, anything illegal. The DEA seized his money. He never got it back.

During the Bush-41 years, Customs Service officials confiscated a small, privately-owned Lear Jet after discovering the plane's owner had made a typographical error on the paperwork he was required to submit to the Federal Aviation Administration before every flight. It was an insignificant error. If it had been caught by the FAA, they would simply have required the plane's owner or pilot to correct the error before starting the flight. But the FAA official doesn't get a 25% bounty on contraband. The Customs official does.

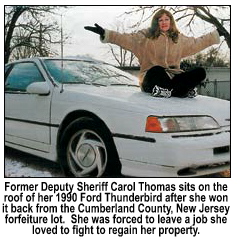

In 1999, Cumberland County,

New Jersey sheriff's deputy Carol Thomas received a call that fellow

deputies from her own department had just arrested her 17-year old son

for selling marijuana to an undercover officer. The Sheriff's Department

seized her 1990 Ford Thunderbird which her son had taken—without

her knowledge or consent—to make his drug sale. He  pleaded

guilty to the charge of selling marijuana. The Sheriff's Department proceeded

with a civil action entitled State of New Jersey v. One 1990 Ford Thunderbird.

The Sheriff—Thomas' boss—went after her car even though

there were no drugs found in the vehicle, and they knew Thomas'

son had taken the car without his mother's permission. A 7-year veteran

of the Sheriff's Department, Thomas quit her job and fought back.

She contacted the Institute For Justice which took the case to

court for her. In a rare victory, the Institute won and Cumberland

County was required to return the title of the car back to Thomas.

But again, not everyone's that lucky.

pleaded

guilty to the charge of selling marijuana. The Sheriff's Department proceeded

with a civil action entitled State of New Jersey v. One 1990 Ford Thunderbird.

The Sheriff—Thomas' boss—went after her car even though

there were no drugs found in the vehicle, and they knew Thomas'

son had taken the car without his mother's permission. A 7-year veteran

of the Sheriff's Department, Thomas quit her job and fought back.

She contacted the Institute For Justice which took the case to

court for her. In a rare victory, the Institute won and Cumberland

County was required to return the title of the car back to Thomas.

But again, not everyone's that lucky.

A New Jersey mother's Oldsmobile was forfeited to police after they arrested her son for shoplifting a pair of pants. A New Jersey construction company was shocked when State Police seized all of its construction equipment. It's crime? State officials decided the company was technically ineligible to bid on three municipal projects that the construction company had already completed.

Kathy and Mark Schrama were arrested a few days before Christmas in 1990 in their New Jersey home. Kathy Schrama was charged with taking UPS packages valued at $500 from neighbor's porches. Mark Schrama was charged with receiving stolen goods at his place of residence. Based on nothing more than a simple accusation from a neighbor who identified Kathy Schrama as the person who took the packages, the police seized the Schrama's $150,000 home—including its furnishings, clothes and the Christmas presents for their 10-year old son. Schrama, who was not wearing his eyeglasses when the police forfeiture squad arrived, was not allowed to take them with him. They had also been seized. The forfeiture took place without due process.

On May 18, 1992, an Iowa woman accused of shoplifting a $25 sweater had her $18,000 car—specially equipped for her handicapped daughter —seized as the "getaway vehicle." The State of Iowa sold her car at auction to help defray the "cost" of prosecuting the woman who actually pleaded no contest to the petty theft and paid the fine and approximately $100 in court costs.

Jennifer

Leigh Ames became the victim of the DEA's legal thieves while

traveling on Amtrak on April 5, 2001. DEA agents thought

she looked suspicious. When they asked if they could check through her

luggage, she said no. They looked anyway. Inside her luggage they found

$640,000 in cash. They found no drugs, nor anything to suggest Ames

was up to anything illegal. But, based on the large sum of cash she was

carrying, they assumed it had to be illegal and seized it.

Jennifer

Leigh Ames became the victim of the DEA's legal thieves while

traveling on Amtrak on April 5, 2001. DEA agents thought

she looked suspicious. When they asked if they could check through her

luggage, she said no. They looked anyway. Inside her luggage they found

$640,000 in cash. They found no drugs, nor anything to suggest Ames

was up to anything illegal. But, based on the large sum of cash she was

carrying, they assumed it had to be illegal and seized it.

Civil forfeiture is the biggest revenue bonanza there is in the States because the State gets to keep 80% of what the seized assets generate at auction. Lawmakers like civil forfeiture because it doesn't cost them any votes on election day (since they assume the people whose assets are seized are criminals who can't, or won't, vote). Civil asset forfeiture is spreading like wildfire across the United States. It has proved to be the best revenue generator since the invention of the printing press even though law enforcement people violate the 4th and 5th Amendments everytime they seize the property of American citizens without due process—regardless of the number of laws legislators pass that give them the authority to do so.

Civil forfeiture is proliferating

largely because of technicalities in the law that allows governments—local,

county, State and federal—to claim it's suing the item of property

that has been seized, and not the owner of the property forfeited. The

lawsuits demand only that the seized goods appear in court, and thus,

the cases show up on courts' dockets' as: US v Parcel of Land at Buena

Vista Ave.; or US v Ten Thousand Dollars in Currency; or US

v 87 Blackheath Road; or New Jersey v. One 1990 Ford Thunderbird.

Prosecutors, with the help of activist

judges in the federal court system have now construed that inanimate objects

have legal standing since the actual owners who have unconstitutionally

been deprived of their property are technically divorced from that property

when it is "forfeited" to the State.

Thanks

to verbal manipulation by politicians and government lawyers, the law

now recognizes parcels of land, houses, construction equipment, motor

vehicles, and cold hard cash as "defendants" under the law.

As such, these "John Does" are subject to "arrest"

when investigating officers believe that the seized property may either

have been, or will be, used in the commission of a crime—or that

it was purchased with ill-gotten gain.

Jointly, the 4th and 5th Amendments

to the Constitution guarantee all American citizens that neither they

nor their property can be seized and detained without due process of law.

Collectively, these two amendments state: "The

right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers and

effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated,

and no warrants shall issue, but upon probable cause, supported by oath

or affirmation, and particularly describing the place to be searched,

and the persons or things to be seized...nor be deprived of life, liberty

or property without due process of law, nor shall private property be

taken for public use, without just compensation."  Because

the property of the people belongs to individual citizens respectively

or collectively, it is constitutionally conjoined to the rights of that

citizen.

Because

the property of the people belongs to individual citizens respectively

or collectively, it is constitutionally conjoined to the rights of that

citizen.

When we weren't paying attention in 1933, a slight of hand by the Roosevelt Administration and the FDR-controlled Congress changed the definition of private property with the single-day passage of the Emergency Banking Relief Act of 1933. A slight modification of the Trading With the Enemy Act of 1917 was incorporated into that legislation which allowed the government to seize all gold that was legally-owned by the American people.

The legislation claimed that the right of the American people to own any property emanated solely from the government. As such, the government could, whenever the need to do so arose, rescind that right and claim any property that previously had rightfully and legally belonged to the people. On March 9, 1933, all Roosevelt and the Fed bankers were concerned about was seizing all of the gold in the legal possession of the people of the United States and replacing their gold and silver-backed currency with a debt-backed federal scrip. It worked. Facing a fine of $10,000 and up to 10-years in prison if they failed to do so, the American people traded their gold certificates for bank notes. To government—any government—a precedent not used is a precedent wasted.

Since the New Deal the federal

government has successfully used Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution

to claim rights it does not constitutionally possess, arguing in court

before generally friendly magistrates that it has a compelling need under

the 9th Amendment to "temporarily" abrogate or infringe upon

the rights of the people because of one national emergency or another.

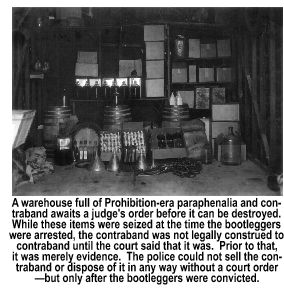

During

the Prohibition years, government agents regularly seized the assets of

organized mobsters who were engaged in the trafficking in bootleg liquor,

but the police lacked the ability to dispose of those items until after

those accused of violating the Volstead Act were prosecuted and

convicted. It made sense to most Americans that the contraband was taken

or destroyed by the feds, since the people clearly understood that home

brew and bootleg whisky were illegal. Therefore, the laws that required

their seizure and destruction made sense. However today, seized assets

are not destroyed. They are converted into cash.

During

the Prohibition years, government agents regularly seized the assets of

organized mobsters who were engaged in the trafficking in bootleg liquor,

but the police lacked the ability to dispose of those items until after

those accused of violating the Volstead Act were prosecuted and

convicted. It made sense to most Americans that the contraband was taken

or destroyed by the feds, since the people clearly understood that home

brew and bootleg whisky were illegal. Therefore, the laws that required

their seizure and destruction made sense. However today, seized assets

are not destroyed. They are converted into cash.

No government—local, county, State or federal—will willingly return forfeited assets once they have been seized since those assets are liquidated as quickly as possible and the money distributed between the appropriate law enforcement agency and the appropriate court, with the seizing agent or police officer receiving his or her "commission"—pretty much like a petty thief taking his stolen wares to the local pawn broker and receiving about 10% of the value.

According to Cary Copeland,

the Justice Department's Director of Asset Forfeiture under President

Bill Clinton (by 1992 the federal government

had actually created a department to handle the growing influx of asset

seizures), when he was called before the House Judiciary Committee

by Chairman Henry Hyde [R-IL] in June, 1993 to discuss the issue

of civil asset forfeitures. "Asset forfeiture is still in its relative infancy as a law enforcement

program." Copeland told the committee, adding that the

FBI under Attorney General Janet Reno anticipated the seizure

of private property would increase at the rate of about 25% a year for

at least three years. Copeland declared that "...asset

forfeiture is to the drug war what smart bombs and air power are to modern

warfare." The use of civil

asset seizure against private citizens by law enforcement was a hurdle

cleared by the US Supreme Court in 1990 when the high court declared it

to be a valid exercise of the prerogative of government which had a compelling

interest in eliminating crime. It was used quite often by the Bush-41

Justice Department.

"Asset forfeiture is still in its relative infancy as a law enforcement

program." Copeland told the committee, adding that the

FBI under Attorney General Janet Reno anticipated the seizure

of private property would increase at the rate of about 25% a year for

at least three years. Copeland declared that "...asset

forfeiture is to the drug war what smart bombs and air power are to modern

warfare." The use of civil

asset seizure against private citizens by law enforcement was a hurdle

cleared by the US Supreme Court in 1990 when the high court declared it

to be a valid exercise of the prerogative of government which had a compelling

interest in eliminating crime. It was used quite often by the Bush-41

Justice Department.

Civil libertarians believed that when Clinton got into the White House, the practice would stop, but Reno found the practice as expedient as Bush's Attorney General, Richard Thornburgh. Civil asset seizures that clearly violated the 4th and 5th Amendments actually increased dramatically under Clinton not only at the federal level, but the practice was eagerly embraced by cash-starved governments at both State and municipal levels as well. There were now more cases in the courts filed against cars, money, houses and other personal property than there were criminal actions filed against living people accused of plotting or committing the crimes for which their property was seized.

Civil asset forfeitures became

so prevalent from 1980 to 1988 that the federal courts began to question

the government's application of Racketeer Influenced & Corrupt

Organizations Act of 1970 [RICO] (an amendment that was added

to the Organized Crime Control Act of 1970) to common citizens.

RICO ended up in front of the 8th Circuit Court of Appeals in 1989.

Judge Richard Arnold of the 8th Circuit curbed the use of RICO

to go after non-crime family related "white collar" criminals.

The

appellate court judge ruled that a pattern of racketeering must exist

and there must be a physical (not suspected) relationship between the

illegal acts of the mobster and the assets which are being seized—and

the likelihood of the criminal activity continuing if the assets are not

seized. The 8th Circuit forced the courts to meet rigid standards before

they could file under RICO, since RICO claims granted the

government an extraordinary windfall—the right to seize all of the

assets of the accused before the commencement of legal action. Generally,

once all of the assets are seized, the defendant no longer possesses the

means to defend himself and finds himself at the mercy of the government's

prosecutors.

The

appellate court judge ruled that a pattern of racketeering must exist

and there must be a physical (not suspected) relationship between the

illegal acts of the mobster and the assets which are being seized—and

the likelihood of the criminal activity continuing if the assets are not

seized. The 8th Circuit forced the courts to meet rigid standards before

they could file under RICO, since RICO claims granted the

government an extraordinary windfall—the right to seize all of the

assets of the accused before the commencement of legal action. Generally,

once all of the assets are seized, the defendant no longer possesses the

means to defend himself and finds himself at the mercy of the government's

prosecutors.

In 1990, on a federal appeal, the Supreme Court overturned the 8th Circuit and reopened the floodgate for the misuse of RICO. The Justice Department argued that the 9th Amendment not only gave them the right, but a compelling need to to stop crime in any form by any means available—even asset seizure without due process. The high court agreed, and actually broadened the powers of the Justice Department under the commerce clause of the Constitution. (What is most interesting about the "commerce clause," is that it is not an implied or specific right granted to the federal government by the Constitution. It is merely an explicatory clarification of the specific, limited rights that had been granted to the federal government and were enumerated below the clarification of how the government was to utilize the limited power granted to it.)

Every unconstitutional act passed by Congress and signed into law by the President of the United States—tons upon countless tons of words over the past 218 years—have been enacted through the broadened powers of the "commerce clause" which says: "The Congress shall have the right to lay and collected taxes, duties, imposts and excises, to pay the debts and provide for the common defense and general welfare of the United States...to regulate commerce with foreign nations and among the several States and with the Indian tribes..." The "commerce clause" has been used by the federal government to seize the assets of American people without due process although there actually are no "rights" here, implied or otherwise. It is merely a preliminary statement authorizing the government to lay and collect taxes in order to defend the country and the welfare of the people. Below that preliminary clause, the authority of the federal government is enumerated.

The government's fidelity to the Constitution of the United States died in 1933. Once the government discovered it could legislatively abrogate the rights of the people without an armed rebellion marching on the nation's capital, it did so—and it has continued to do so for 72 years. As the federal bureaucracy has proven over the last seven decades, the restraints on the ability of government to enact whatever laws it wishes—as long as they are supported by a popular majority—are virtually nonexistent even if the laws they enact violate the tenets of the Constitution and the Bill of Rights.

But occasionally, even Congress knows when its gone too far. By 1992, with the House Judiciary Committee examining the ramifications of civil asset forfeiture, the Justice Department realized it had to reign in its own law enforcement agencies—or at least make it appear they were. In its 1992 annual report on asset seizures, the Justice Department declared that "...[n]o property may be seized unless the government has probable cause to believe that it is subject to forfeiture." That clarification arose from the fact that far too many federal seizures were being made based on "hearsay" information—rumors and neighborhood gossip based on "suspicions" about private neighbors from anonymous sources. Hearsay evidence cannot be admitted into a court of law, but it was being used by the DEA and the FBI to seize the assets of American citizens with few of those Americans ever being arrested for the crimes they were suspected of committing.

Police agencies routinely refuse

to identity "sources" who finger specific targets for seizures.

In some cases, the rumors are made up by the police themselves because

someone in the department or the city government wanted a particular home,

vehicle, or other asset that was suddenly targeted for seizure. The Fort

Lauderdale, Florida police seized the $250 thousand riverfront home of

a man who had just died from cancer. The

reason for the seizure? A confidential informant told the police that,

two years earlier, the owner of the house had taken a $10 thousand payment

from some drug dealers who used his dock to unload a shipment of cocaine.

The informant did not know who the drug dealers were, didn't know the

name of the boat that supposedly transported the drugs to Florida, nor

did the informant have any idea of the approximate date when the incident

supposedly took place.  With

nothing more than a vague rumor that the owner was involved in a drug

transaction a couple of years earlier, and with absolutely no evidence

that drugs had ever been offloaded on the man's dock, the police seized

the home from the man's heirs.

With

nothing more than a vague rumor that the owner was involved in a drug

transaction a couple of years earlier, and with absolutely no evidence

that drugs had ever been offloaded on the man's dock, the police seized

the home from the man's heirs.

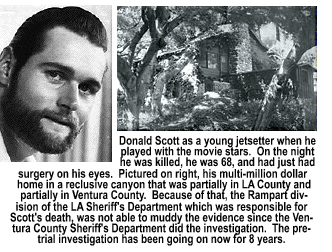

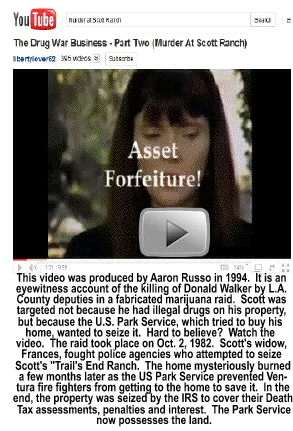

But that incident is not as bad as the one in which a Malibu, California heir to a European chemical fortune, Donald Scott, was shot to death on October 2, 1992 by LA County sheriff's deputies in a forfeiture raid on his plush ranch. When the story broke in October, 1992, reports leaked out that an official in the US Forest Service wanted the house and believed he could buy it "cheap" in a forfeiture sale. The claim, identifying the official, appeared once in print. The story quickly died and did not resurface. It had "lawsuit" written all over it.

Two US Park Service employees—Ranger

Mike Alt and Special Agent Laurel Pistel—were asked

to attend a meeting with the LA Sheriff's Rampart Division to discuss

marijuana cases. Pistel told the media that she heard Scott's

Trail's End Ranch mentioned during the meeting, but added that

she did not recall asset forfeiture being discussed by anyone.  A

raid was planned for that evening. In the meeting aerial photographs of

Scott's land were displayed, purportedly supporting the contention

that the millionaire was growing marijuana on his land. However, no one

could identify anything that resembled the 4,000 cannabis plants that

were supposed to be there. The only thing the photos showed was an irrigation

system on the property that appeared to have been channeled from a nearby

National Park that, according to Alt may or may not have been illegal.

There was certainly nothing there that would allow anyone to raid Scott's

ranch, let alone seize his property.

A

raid was planned for that evening. In the meeting aerial photographs of

Scott's land were displayed, purportedly supporting the contention

that the millionaire was growing marijuana on his land. However, no one

could identify anything that resembled the 4,000 cannabis plants that

were supposed to be there. The only thing the photos showed was an irrigation

system on the property that appeared to have been channeled from a nearby

National Park that, according to Alt may or may not have been illegal.

There was certainly nothing there that would allow anyone to raid Scott's

ranch, let alone seize his property.

Late that night 31 sheriff's deputies and federal agents from no less than five agencies broke down their door and stormed into the house. Frances Scott heard the initial crash and bolted from her bedroom, heading down the stairs only to be greeted by a horde of armed, masked men charging up the stairs—right at her. She screamed. This brought 68-year old Donald Scott—who had cataract surgery earlier that day—out of the bedroom with a gun in hand. Half-blind, Scott ran to the sound of voices to defend his wife. He got as far as the stairwell and was shot dead. Other than as blurs, he likely never saw the men who killed him.

The forfeiture warrant allowed

the DEA, FBI and Sheriff's deputies to search his home and

property for evidence of marijuana. None was found. No signs of any form

of illegal activity was found on the Scott ranch—except the

diverted water from the National Park. And that certainly was not a capital

offense. .jpg) Since

Scott's ranch was primarily located in Ventura County and not LA

County, the Ventura Sheriff's Department claimed jurisdiction to investigate

the shooting. After a thorough investigation, Ventura County District

Attorney Michael Bradbury concluded that the LA Sheriff's Department

had lied to a judge to obtain the search warrant that brought them to

Trail's End on the night of Oct. 2, 1992. Bradbury further

stated that there was no evidence that there had ever been any marijuana

grown anywhere on Scott's property, and that the raid was instigated

by someone whose intent was to forfeit the multi-million dollar ranch.

Frances Scott has filed a $100 million lawsuit against the LA Sheriff's

Department and the deputies who actually killed her husband.

Since

Scott's ranch was primarily located in Ventura County and not LA

County, the Ventura Sheriff's Department claimed jurisdiction to investigate

the shooting. After a thorough investigation, Ventura County District

Attorney Michael Bradbury concluded that the LA Sheriff's Department

had lied to a judge to obtain the search warrant that brought them to

Trail's End on the night of Oct. 2, 1992. Bradbury further

stated that there was no evidence that there had ever been any marijuana

grown anywhere on Scott's property, and that the raid was instigated

by someone whose intent was to forfeit the multi-million dollar ranch.

Frances Scott has filed a $100 million lawsuit against the LA Sheriff's

Department and the deputies who actually killed her husband.

The lawsuit was resolved. Scott's Trail's End home caught fire a few months after his death. Park Service officials refused to allow Ventura County fire engines near the home. It burned to the ground. Ultimately, the Internal Revenue Service seized the property for nonpayment of taxes. The US government assessed a Death Tax on the estate, computed on the value of Scott's foreign inheritance. Not paid as Frances Scott struggled to pursue her lawsuit against Los Angeles County, the penalties and interest on the IRS lien pyramided until the IRS seized every asset possessed by Donald Scott's estate—which, of course included everything in the world the widow possessed. Left virtually penniless, she could no longer pursue her lawsuit against the deputies who wrongfully killed her husband.

The Scott killing created

national headlines. One of those who read the headline was Congressman

Henry Hyde [R-IL]. Civil asset forfeiture had been a reform in

the center of Hyde's plate for almost seven years. In 1992 federal law

enforcement agencies seized $450 million in personal assets from American

citizens using civil asset forfeiture proceedings that pretty much leave

the human defendant penniless and unable to fight the forfeiture in court.

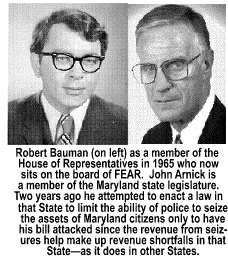

Robert Bauman, a former Republican US Congressman from Maryland

who now serves on the Board of Directors of FEAR [Forfeiture

Endangers American Rights], a Washington, DC advocacy group, said

conservatively, $7 to $8 billion in seized asset bonuses have been split

between the various federal, state and local police agencies over the

past two decades.  What

troubled Bauman—and Henry Hyde—was that aside

from one or two States that turned their "commissions" over

to the State treasury, most police departments got to keep the money.

And that presented an unacceptable conflict of interest. After Frederick,

Maryland police seized the 1988 Toyota pickup of a local resident after

he purchased a $40 drug placebo in a police department sting, Maryland

Delegate John Arnick proposed a law to reform Maryland's forfeiture

laws by adding a section on defendant rights. The House of Delegates denounced

his legislation, calling it a crazy law that's "..going to inconvenience

the hell out of everyone" by making the cops appear in court

and testify why they seized someone's property. The legislators thought

the existing law was good because it allowed the owner of the property

to buy their property back at one-half the appraised value.

What

troubled Bauman—and Henry Hyde—was that aside

from one or two States that turned their "commissions" over

to the State treasury, most police departments got to keep the money.

And that presented an unacceptable conflict of interest. After Frederick,

Maryland police seized the 1988 Toyota pickup of a local resident after

he purchased a $40 drug placebo in a police department sting, Maryland

Delegate John Arnick proposed a law to reform Maryland's forfeiture

laws by adding a section on defendant rights. The House of Delegates denounced

his legislation, calling it a crazy law that's "..going to inconvenience

the hell out of everyone" by making the cops appear in court

and testify why they seized someone's property. The legislators thought

the existing law was good because it allowed the owner of the property

to buy their property back at one-half the appraised value.

In 1993—when the Newt

Gingrich-inspired "Contract With America" gave the

GOP control of Congress, Hyde introduced HR315, The Civil

Forfeiture Reform Act of 1993. The proposed legislation would shift

the burden of proof from the defendant to the government, and provide

counsel for indigent defendants whose assets were seized and who couldn't

afford legal representation. And, most of all, it allowed those who won

back their property in court to sue the government for damages. HR315

passed in the House of Representatives, but died in its fetal stages in

the Senate. .jpg) The

more liberal US Senate pretty much took the same view as the Maryland

legislature— its an easy way to generate revenue for the government

without raising taxes.

The

more liberal US Senate pretty much took the same view as the Maryland

legislature— its an easy way to generate revenue for the government

without raising taxes.

Hyde did not give up. He ramped up the bill again in 1995, adding a couple of new twists that the bureaucrats didn't like any better in 1995 than they did in 1993. The Civil Forfeiture Reform Act of 1995 would require whomever seized the defendant's property to return it until the case was decided in federal court and the federal judge—not by some local cop, deputy sheriff, state cop or DEA agent working on commission. In addition, the new law would eliminate the requirement that the litigant post a bond to cover the cost of the proceedings in order to sue the government. A watered-down version of the bill was finally enacted in 2000. Clinton signed the bill into law to help Al Gore during his campaign against George W. Bush. But The Civil Forfeiture Reform Act of 2000 did little to solve the problems. But it made it appear that Congress was diligently working to control how RICO was applied against average American citizens when it really wasn't. What the right hand giveth, the left hand always takes away..

On March 20, 2002 Colorado State Senator Bill Theibaut and State legislator Shawn Mitchell introduced legislation in that State to curb the power of the bureaucracy to confiscate the property of Coloradoans without due process. More and more States are now looking at the "gift horse" that makes up the shortfalls in the State's budget and are realizing that, in far too many instances, the men wearing badges should actually be wearing masks—and they should be the ones arrested for theft. Particularly those police agencies that use sting operations to snare marijuana and crack cocaine users by selling them drugs or drug placebos—and then seizing the cars of those they trap or, seizing the cars of "johns" who approach—or, more often, are approached by—female police officers posing as prostitutes. Entrapment is bad enough, but seizing the cars of those snared by trickery when the drugs they are buying are not real drugs, and the prostitutes they proposition are not real prostitutes raises serious questions about the legitimacy of the forfeitures...even if the seizures do not technically violate the 4th and 5th amendments because government feels it has a compelling need to "test" the moral character of its citizens to see if they will commit a crime if the opportunity presents itself.

Copyright © 2009 Jon Christian Ryter.

All rights reserved.